【翻译中】AI算力民主化(译文)

原作者:Chris Lattner

- 第一部分:DeepSeek 给 AI 带来的影响

- 第二部分:CUDA 到底是什么?

- 第三部份:CUDA 是如何成功的?

- 第四部分:CUDA 现在是主流,但它真的够好吗?

- 第五部份:CUDA C++ 的替代品(比如 OpenCL)如何?

- 第六部分:AI 编译器(TVM、XLA)如何?

- 第七部分:Triton 等 Python DSL 语言如何?

- 第八部份:MLIR 编译器基础设施如何?

- 第九部分:为什么硬件公司难以构建 AI 软件?

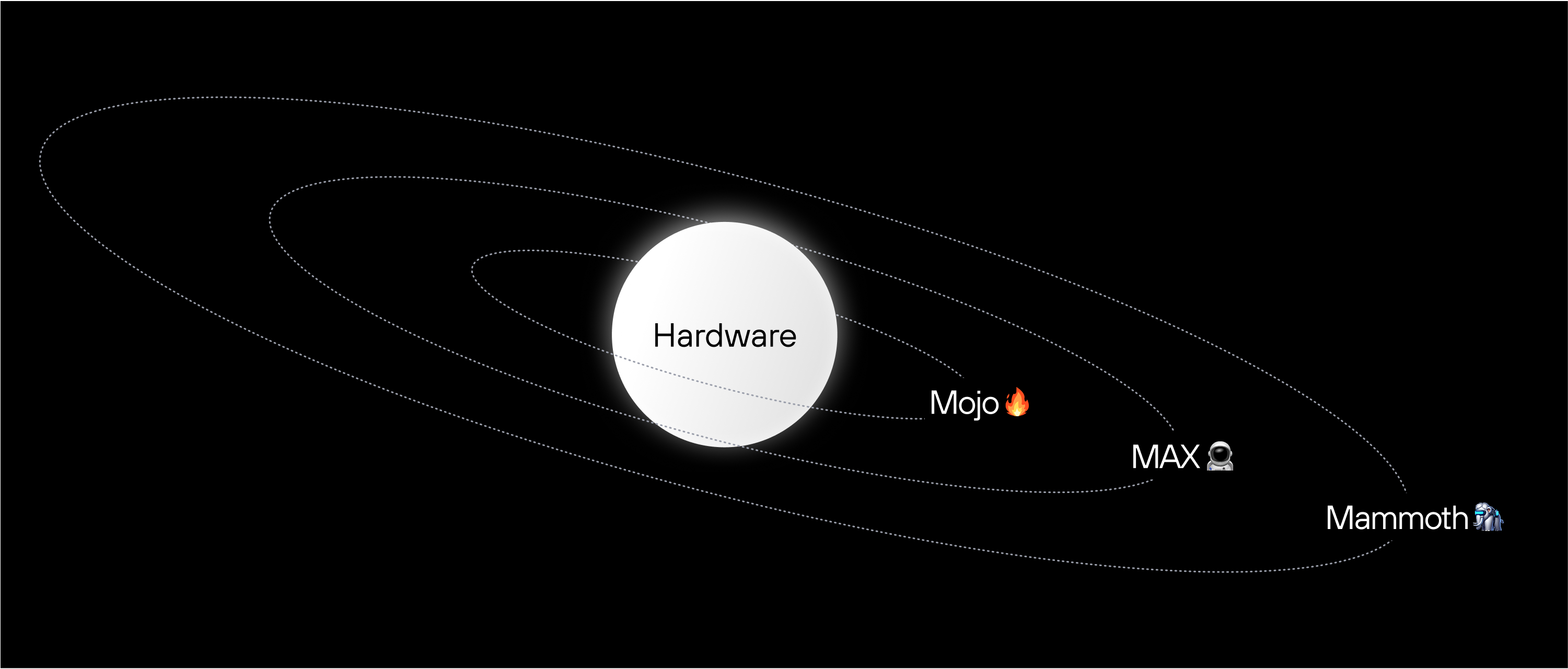

- 第十部分:Modular 突破“矩阵”的决心

- 第十一部分: Modular 是如何让 AI 算力民主化的?

Democratizing AI Compute, Part 1: DeepSeek’s Impact on AI

DeepSeek’s recent breakthrough has upended assumptions about AI’s compute demands, showing that better hardware utilization can dramatically reduce the need for expensive GPUs.

For years, leading AI companies have insisted that only those with vast compute resources can drive cutting-edge research, reinforcing the idea that it is “hopeless to catch up” unless you have billions of dollars to spend on infrastructure. But DeepSeek’s success tells a different story: novel ideas can unlock efficiency breakthroughs to accelerate AI, and smaller, highly focused teams to challenge industry giants–and even level the playing field.

We believe DeepSeek’s efficiency breakthrough signals a coming surge in demand for AI applications. If AI is to continue advancing, we must drive down the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)–by expanding access to alternative hardware, maximizing efficiency on existing systems, and accelerating software innovation. Otherwise, we risk a future where AI’s benefits are bottlenecked–either by hardware shortages or by developers struggling to effectively utilize the diverse hardware that is available.

This isn’t just an abstract problem–it’s a challenge I’ve spent my career working to solve.

My passion for compute + developer efficiency

I’ve spent the past 25 years working to unlock computing power for the world. I founded and led the development of LLVM, a compiler technology that opened CPUs to new applications of compiler technology. Today, LLVM is the foundation for performance-oriented programming languages like C++, Rust, Swift and more. It powers nearly all iOS and Android apps, as well as the infrastructure behind major internet services from Google and Meta.

This work paved the way for several key innovations I led at Apple, including the creation of OpenCL, an early accelerator framework now widely adopted across the industry, the rebuild of Apple’s CPU and GPU software stack using LLVM, and the development of the Swift programming language. These experiences reinforced my belief in the power of shared infrastructure, the importance of co-designing hardware and software, and how intuitive, developer-friendly tools unlock the full potential of advanced hardware.

Falling in love with AI

In 2017, I became fascinated by AI’s potential and joined Google to lead software development for the TPU platform. At the time, the hardware was ready, but the software wasn’t functional. Over the next two and a half years, through intense team effort, we launched TPUs in Google Cloud, scaled them to ExaFLOPS of compute, and built a research platform that enabled breakthroughs like Attention Is All You Need and BERT.

Yet, this journey revealed deeper troubles in AI software. Despite TPUs’ success, they remain only semi-compatible with AI frameworks like PyTorch–an issue Google overcomes with vast economic and research resources. A common customer question was, “Can TPUs run arbitrary AI models out of the box?” The hard truth? No–because we didn’t have CUDA, the de facto standard for AI development.

I’m not one to shy away from tackling major industry problems: my recent work has been the creation of next-generation technologies to scale into this new era of hardware and accelerators. This includes the MLIR compiler framework (widely adopted now for AI compilers across the industry) and the Modular team has spent the last 3 years building something special–but we’ll share more about that later, when the time is right.

How do GPUs and next-generation compute move forward?

Because of my background and relationships across the industry, I’m often asked about the future of compute. Today, countless groups are innovating in hardware (fueled in part by NVIDIA’s soaring market cap), while many software teams are adopting MLIR to enable new architectures. At the same time, senior leaders are questioning why–despite massive investments–the AI software problem remains unsolved. The challenge isn’t a lack of motivation or resources. So why does the industry feel stuck?

I don’t believe we are stuck. But we do face difficult, foundational problems.

To move forward, we need to better understand the underlying industry dynamics. Compute is a deeply technical field, evolving rapidly, and filled with jargon, codenames, and press releases designed to make every new product sound revolutionary. Many people try to cut through the noise to see the forest for the trees, but to truly understand where we’re going, we need to examine the roots—the fundamental building blocks that hold everything together.

This post is the first in a multipart series where we’ll help answer these critical questions in a straightforward, accessible way:

- 🧐 What exactly is CUDA?

- 🎯 Why has CUDA been so successful?

- ⚖️ Is CUDA any good?

- ❓ Why do other hardware makers struggle to provide comparable AI software?

- ⚡ Why haven’t existing technologies like Triton or OneAPI or OpenCL solved this?

- 🚀 How can we as an industry move forward?

I hope this series sparks meaningful discussions and raises the level of understanding around these complex issues. The rapid advancements in AI—like DeepSeek’s recent breakthroughs–remind us that software and algorithmic innovation are still driving forces. A deep understanding of low-level hardware continues to unlock “10x” breakthroughs.

AI is advancing at an unprecedented pace–but there’s still so much left to unlock. Together we can break it down, challenge assumptions, and push the industry forward. Let’s dive in!

Democratizing AI Compute, Part 2: What exactly is “CUDA”?

It seems like everyone has started talking about CUDA in the last year: It’s the backbone of deep learning, the reason novel hardware struggles to compete, and the core of NVIDIA’s moat and soaring market cap. With DeepSeek, we got a startling revelation: its breakthrough was made possible by “bypassing” CUDA, going directly to the PTX layer… but what does this actually mean? It feels like everyone wants to break past the lock-in, but we have to understand what we’re up against before we can formulate a plan.

moat: 护城河

CUDA’s dominance in AI is undeniable—but most people don’t fully understand what CUDA actually is. Some think it’s a programming language. Others call it a framework. Many assume it’s just “that thing NVIDIA uses to make GPUs faster.” None of these are entirely wrong—and many brilliant people are trying to explain this—but none capture the full scope of “The CUDA Platform.”

CUDA is not just one thing. It’s a huge, layered Platform—a collection of technologies, software libraries, and low-level optimizations that together form a massive parallel computing ecosystem. It includes:

- A low-level parallel programming model that allows developers to harness the raw power of GPUs with a C++-like syntax.

- A complex set of libraries and frameworks—middleware that powers crucial vertical use cases like AI (e.g., cuDNN for PyTorch and TensorFlow).

- A suite of high-level solutions like TensorRT-LLM and Triton, which enable AI workloads (e.g., LLM serving) without requiring deep CUDA expertise.

…and that’s just scratching the surface.

In this article, we’ll break down the key layers of the CUDA Platform, explore its historical evolution, and explain why it’s so integral to AI computing today. This sets the stage for the next part in our series, where we’ll dive into why CUDA has been so successful. Hint: it has a lot more to do with market incentives than it does the technology itself.

Let’s dive in. 🚀

The Road to CUDA: From Graphics to General-Purpose Compute

Before GPUs became the powerhouses of AI and scientific computing, they were graphics processors—specialized processors for rendering images. Early GPUs hardwired image rendering into silicon, meaning that every step of rendering (transformations, lighting, rasterization) was fixed. While efficient for graphics, these chips were inflexible—they couldn’t be repurposed for other types of computation.

Everything changed in 2001 when NVIDIA introduced the GeForce3, the first GPU with programmable shaders. This was a seismic shift in computing:

- 🎨 Before: Fixed-function GPUs could only apply pre-defined effects.

- 🖥️ After: Developers could write their own shader programs, unlocking programmable graphics pipelines.

This advancement came with Shader Model 1.0, allowing developers to write small, GPU-executed programs for vertex and pixel processing. NVIDIA saw where the future was heading: instead of just improving graphics performance, GPUs could become programmable parallel compute engines.

At the same time, it didn’t take long for researchers to ask:

“🤔 If GPUs can run small programs for graphics, could we use them for non-graphics tasks?”

One of the first serious attempts at this was the BrookGPU project at Stanford. Brook introduced a programming model that let CPUs offload compute tasks to the GPU—a key idea that set the stage for CUDA.

This move was strategic and transformative. Instead of treating compute as a side experiment, NVIDIA made it a first-class priority, embedding CUDA deeply into its hardware, software, and developer ecosystem.

The CUDA Parallel Programming Model

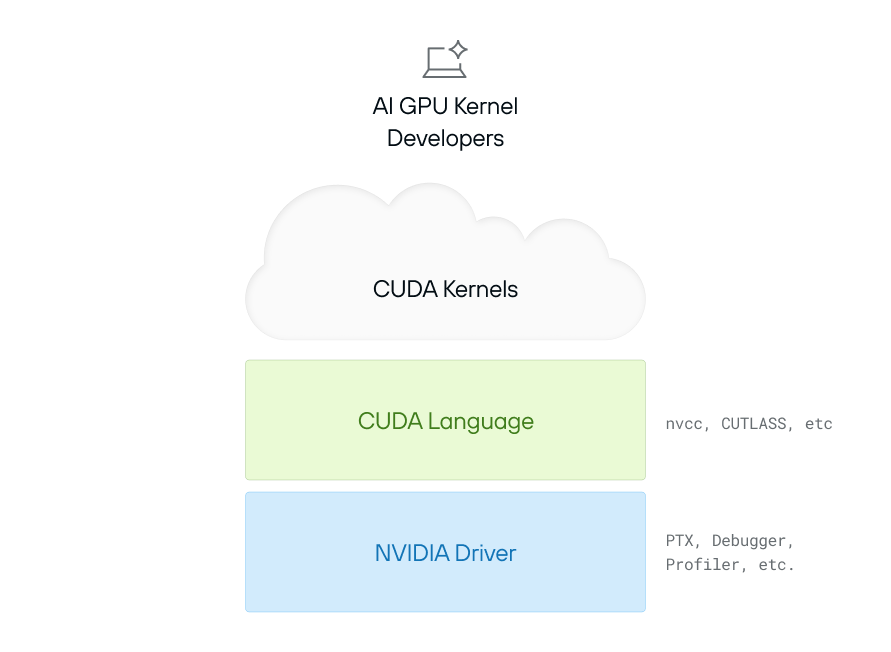

In 2006, NVIDIA launched CUDA (”Compute Unified Device Architecture”)—the first general-purpose programming platform for GPUs. The CUDA programming model is made up of two different things: the “CUDA programming language”, and the “NVIDIA Driver”.

CUDA is a Layered Stack Requiring Deep Integration from Driver to Kernel

The CUDA language is derived from C++, with enhancements to directly expose low-level features of the GPU—e.g. its ideas of “GPU threads” and memory. A programmer can use this language to define a “CUDA Kernel”—an independent calculation that runs on the GPU. A very simple example is:

__global__ void addVectors(float *a, float *b, float *c, int n) {

int idx = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

if (idx < n) {

c[idx] = a[idx] + b[idx];

}

}

CUDA kernels allow programmers to define a custom computation that accesses local resources (like memory) and using the GPUs as very fast parallel compute units. This language is translated (”compiled”) down to “PTX”, which is an assembly language that is the lowest level supported interface to NVIDIA GPUs.

But how does a program actually execute code on a GPU? That’s where the NVIDIA Driver comes in. It acts as the bridge between the CPU and the GPU, handling memory allocation, data transfers, and kernel execution. A simple example is:

cudaMalloc(&d_A, size);

cudaMalloc(&d_B, size);

cudaMalloc(&d_C, size);

cudaMemcpy(d_A, A, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

cudaMemcpy(d_B, B, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

int threadsPerBlock = 256;

// Compute the ceiling of N / threadsPerBlock

int blocksPerGrid = (N + threadsPerBlock - 1) / threadsPerBlock;

addVectors<<<blocksPerGrid, threadsPerBlock>>>(d_A, d_B, d_C, N);

cudaMemcpy(C, d_C, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

cudaFree(d_A);

cudaFree(d_B);

cudaFree(d_C);

Note that all of this is very low level—full of fiddly details (e.g. pointers and “magic numbers”). If you get something wrong, you’re most often informed of this by a difficult to understand crash. Furthermore, CUDA exposes a lot of details that are specific to NVIDIA hardware—things like the “number of threads in a warp” (which we won’t explore here).

Despite the challenges, these components enabled an entire generation of hardcore programmers to get access to the huge muscle that a GPU can apply to numeric problems. For example, the AlexNET ignited modern deep learning in 2012. It was made possible by custom CUDA kernels for AI operations like convolution, activations, pooling and normalization and the horsepower a GPU can provide.

While the CUDA language and driver are what most people typically think of when they hear “CUDA,” this is far from the whole enchilada—it’s just the filling inside. Over time, the CUDA Platform grew to include much more, and as it did, the meaning of the original acronym fell away from being a useful way to describe CUDA.

High-Level CUDA Libraries: Making GPU Programming More Accessible

The CUDA programming model opened the door to general-purpose GPU computing and is powerful, but it brings two challenges:

- CUDA is difficult to use, and even worse…

- CUDA doesn’t help with performance portability

Most kernels written for generation N will “keep working” on generation N+1, but often the performance is quite bad—far from the peak of what N+1 generation can deliver, even though GPUs are all about performance. This makes CUDA a strong tool for expert engineers, but a steep learning curve for most developers. But is also means that significant rewrites are required every time a new generation of GPU comes out (e.g. Blackwell is now emerging).

As NVIDIA grew it wanted GPUs to be useful to people who were domain experts in their own problem spaces, but weren’t themselves GPU experts. NVIDIA’s solution to this problem was to start building rich and complicated closed-source, high-level libraries that abstract away low-level CUDA details. These include:

- cuDNN (2014) – Accelerates deep learning (e.g., convolutions, activation functions).

- cuBLAS – Optimized linear algebra routines.

- cuFFT – Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT) on GPUs.

- … and many others.

With these libraries, developers could tap into CUDA’s power without needing to write custom GPU code, with NVIDIA taking on the burden of rewriting these for every generation of hardware. This was a big investment from NVIDIA, but it worked.

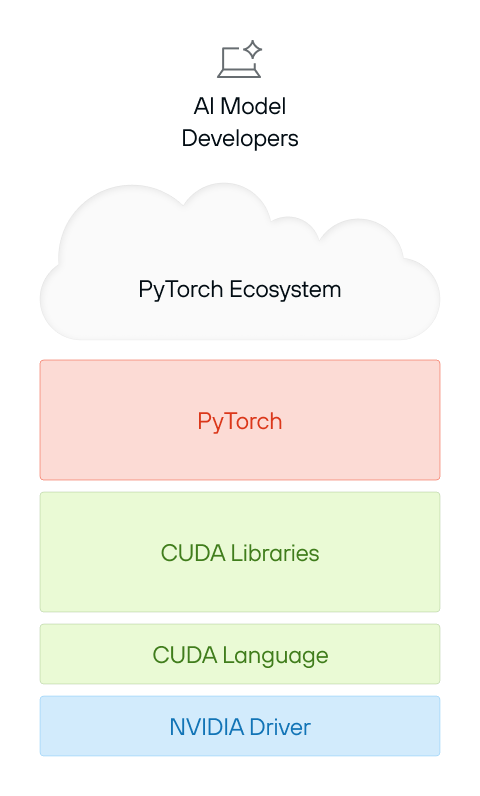

The cuDNN library is especially important in this story—it paved the way for Google’s TensorFlow (2015) and Meta’s PyTorch (2016), enabling deep learning frameworks to take off. While there were earlier AI frameworks, these were the first frameworks to truly scale—modern AI frameworks now have thousands of these CUDA kernels and each is very difficult to write. As AI research exploded, NVIDIA aggressively pushed to expand these libraries to cover the important new use-cases.

PyTorch on CUDA is Built on Multiple Layers of Dependencies

NVIDIA’s investment into these powerful GPU libraries enabled the world to focus on building high-level AI frameworks like PyTorch and developer ecosystems like HuggingFace. Their next step was to make entire solutions that could be used out of the box—without needing to understand the CUDA programming model at all.

Fully vertical solutions to ease the rapid growth of AI and GenAI

The AI boom went far beyond research labs—AI is now everywhere. From image generation to chatbots, from scientific discovery to code assistants, Generative AI (GenAI) has exploded across industries, bringing a flood of new applications and developers into the field.

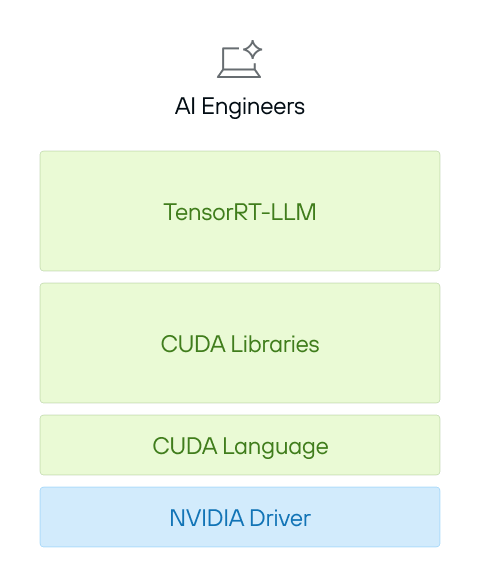

At the same time, a new wave of AI developers emerged, with very different needs. In the early days, deep learning required highly specialized engineers who understood CUDA, HPC, and low-level GPU programming. Now, a new breed of developer—often called AI engineers—is building and deploying AI models without needing to touch low-level GPU code.

To meet this demand, NVIDIA went beyond just providing libraries—it now offers turnkey solutions that abstract away everything under the hood. Instead of requiring deep CUDA expertise, these frameworks allow AI developers to optimize and deploy models with minimal effort.

- Triton Serving – A high-performance serving system for AI models, allowing teams to efficiently run inference across multiple GPUs and CPUs.

- TensorRT – A deep learning inference optimizer that automatically tunes models to run efficiently on NVIDIA hardware.

- TensorRT-LLM – An even more specialized solution, built for large language model (LLM) inference at scale.

- … plus many (many) other things.

Several Layers Exist Between NVIDIA Drivers and TensorRT-LLM

These tools completely shield AI engineers from CUDA’s low-level complexity, letting them focus on AI models and applications, not hardware details. These systems provide significant leverage which has enabled the horizontal scale of AI applications.

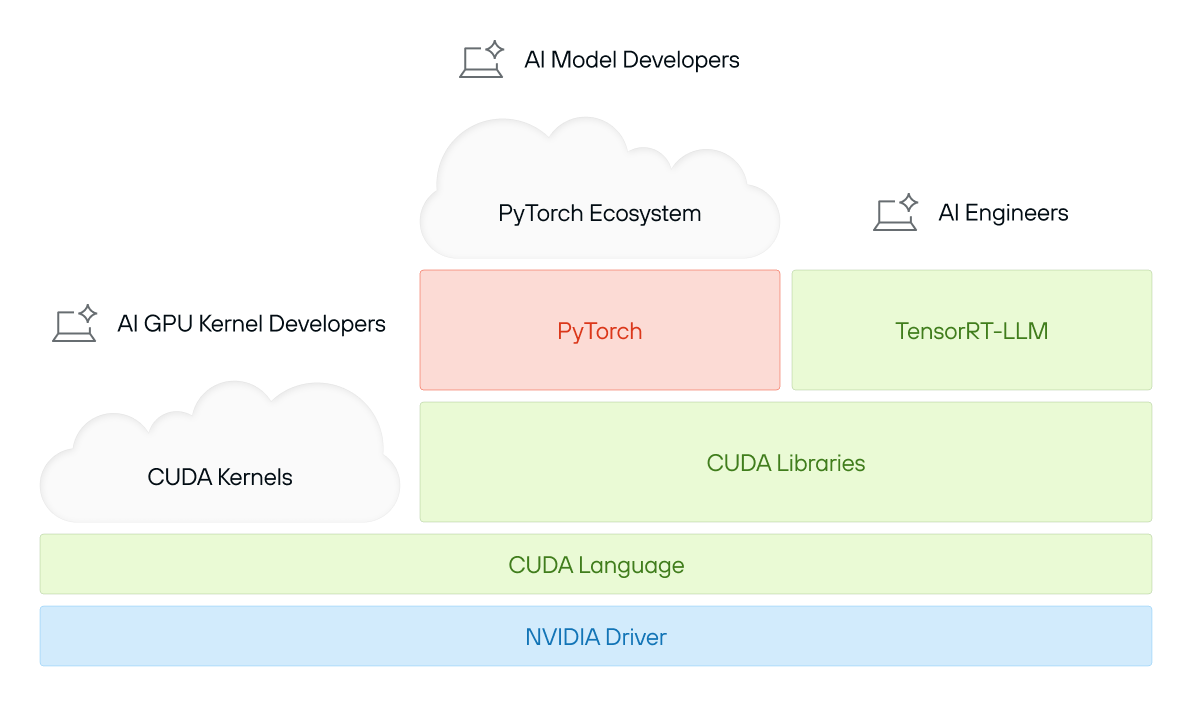

The “CUDA Platform” as a whole

CUDA is often thought of as a programming model, a set of libraries, or even just “that thing NVIDIA GPUs run AI on.” But in reality, CUDA is much more than that—it is a unifying brand, a truly vast collection of software, and a highly tuned ecosystem, all deeply integrated with NVIDIA’s hardware. For this reason, the term “CUDA” is ambiguous—we prefer the term “The CUDA Platform” to clarify that we’re talking about something closer in spirit to the Java ecosystem, or even an operating system, than merely a programming language and runtime library.

CUDA’s Expanding Complexity: A Multi-Layered Ecosystem Spanning Drivers, Languages, Libraries, and Frameworks

At its core, the CUDA Platform consists of:

- A massive codebase – Decades of optimized GPU software, spanning everything from matrix operations to AI inference.

- A vast ecosystem of tools & libraries – From cuDNN for deep learning to TensorRT for inference, CUDA covers an enormous range of workloads.

- Hardware-tuned performance – Every CUDA release is deeply optimized for NVIDIA’s latest GPU architectures, ensuring top-tier efficiency.

- Proprietary and opaque – When developers interact with CUDA’s library APIs, much of what happens under the hood is closed-source and deeply tied to NVIDIA’s ecosystem.

CUDA is a powerful but sprawling set of technologies—an entire software platform that sits at the foundation of modern GPU computing, even going beyond AI specifically.

Now that we know what “CUDA” is, we need to understand how it got to be so successful. Here’s a hint: CUDA’s success isn’t really about performance—it’s about strategy, ecosystem, and momentum. In the next post, we’ll explore what enabled NVIDIA’s CUDA software to shape and entrench the modern AI era.

See you next time. 🚀

Democratizing AI Compute, Part 3: How did CUDA succeed?

If we as an ecosystem hope to make progress, we need to understand how the CUDA software empire became so dominant. On paper, alternatives exist—AMD’s ROCm, Intel’s oneAPI, SYCL-based frameworks—but in practice, CUDA remains the undisputed king of GPU compute.

How did this happen?

The answer isn’t just about technical excellence—though that plays a role. CUDA is a developer platform built through brilliant execution, deep strategic investment, continuity, ecosystem lock-in, and, of course, a little bit of luck.

This post breaks down why CUDA has been so successful, exploring the layers of NVIDIA’s strategy—from its early bets on generalizing parallel compute to the tight coupling of AI frameworks like PyTorch and TensorFlow. Ultimately, CUDA’s dominance is not just a triumph of software but a masterclass in long-term platform thinking.

Let’s dive in. 🚀

The Early Growth of CUDA

A key challenge of building a compute platform is attracting developers to learn and invest in it, and it is hard to gain momentum if you can only target niche hardware. In a great “Acquired” podcast, Jensen Huang shares that a key early NVIDIA strategy was to keep their GPUs compatible across generations. This enabled NVIDIA to leverage its install base of already widespread gaming GPUs, which were sold for running DirectX-based PC games. Furthermore, it enabled developers to learn CUDA on low-priced desktop PCs and scale into more powerful hardware that commanded high prices.

This might seem obvious now, but at the time it was a bold bet: instead of creating separate product lines optimized for different use-cases (laptops, desktops, IoT, datacenter, etc.), NVIDIA built a single contiguous GPU product line. This meant accepting trade-offs—such as power or cost inefficiencies—but in return, it created a unified ecosystem where every developer’s investment in CUDA could scale seamlessly from gaming GPUs to high-performance datacenter accelerators. This strategy is quite analogous to how Apple maintains and drives its iPhone product line forward.

The benefits of this approach were twofold:

- Lowering Barriers to Entry – Developers could learn CUDA using the GPUs they already had, making it easy to experiment and adopt.

- Creating a Network Effect – As more developers started using CUDA, more software and libraries were created, making the platform even more valuable.

This early install base allowed CUDA to grow beyond gaming into scientific computing, finance, AI, and high-performance computing (HPC). Once CUDA gained traction in these fields, its advantages over alternatives became clear: NVIDIA’s continued investment ensured that CUDA was always at the cutting edge of GPU performance, while competitors struggled to build a comparable ecosystem.

Catching and Riding the Wave of AI Software

CUDA’s dominance was cemented with the explosion of deep learning. In 2012, AlexNet, the neural network that kickstarted the modern AI revolution, was trained using two NVIDIA GeForce GTX 580 GPUs. This breakthrough not only demonstrated that GPUs were faster at deep learning—it proved they were essential for AI progress and led to CUDA’s rapid adoption as the default compute backend for deep learning.

As deep learning frameworks emerged—most notably TensorFlow (Google, 2015) and PyTorch (Meta, 2016)—NVIDIA seized the opportunity and invested heavily in optimizing its High-Level CUDA Libraries to ensure these frameworks ran as efficiently as possible on its hardware. Rather than leaving AI framework teams to handle low-level CUDA performance tuning themselves, NVIDIA took on the burden by aggressively refining cuDNN and TensorRT as we discussed in Part 2.

This move not only made PyTorch and TensorFlow significantly faster on NVIDIA GPUs—it also allowed NVIDIA to tightly integrate its hardware and software (a process known as “hardware/software co-design”) because it reduced coordination with Google and Meta. Each major new generation of hardware would come out with a new version of CUDA that exploited the new capabilities of the hardware. The AI community, eager for speed and efficiency, was more than willing to delegate this responsibility to NVIDIA—which directly led to these frameworks being tied to NVIDIA hardware.

But why did Google and Meta let this happen? The reality is that Google and Meta weren’t singularly focused on building a broad AI hardware ecosystem—they were focused on using AI to drive revenue, improve their products, and unlock new research. Their top engineers prioritized high-impact internal projects to move internal company metrics. For example, these companies decided to build their own proprietary TPU chips—pouring their effort into optimizing for their own first-party hardware. It made sense to give the reins to NVIDIA for GPUs.

Makers of alternative hardware faced an uphill battle—trying to replicate the vast, ever-expanding NVIDIA CUDA library ecosystem without the same level of consolidated hardware focus. Rival hardware vendors weren’t just struggling—they were trapped in an endless cycle, always chasing the next AI advancement on NVIDIA hardware. This impacted Google and Meta’s in-house chip projects as well, which led to numerous projects, including XLA and PyTorch 2. We can dive into these deeper in subsequent articles, but despite some hopes, we can see today that nothing has enabled hardware innovators to match the capabilities of the CUDA platform.

With each generation of its hardware, NVIDIA widened the gap. Then suddenly, in late 2022, ChatGPT exploded onto the scene, and with it, GenAI and GPU compute went mainstream.

Capitalizing on the Generative AI Surge

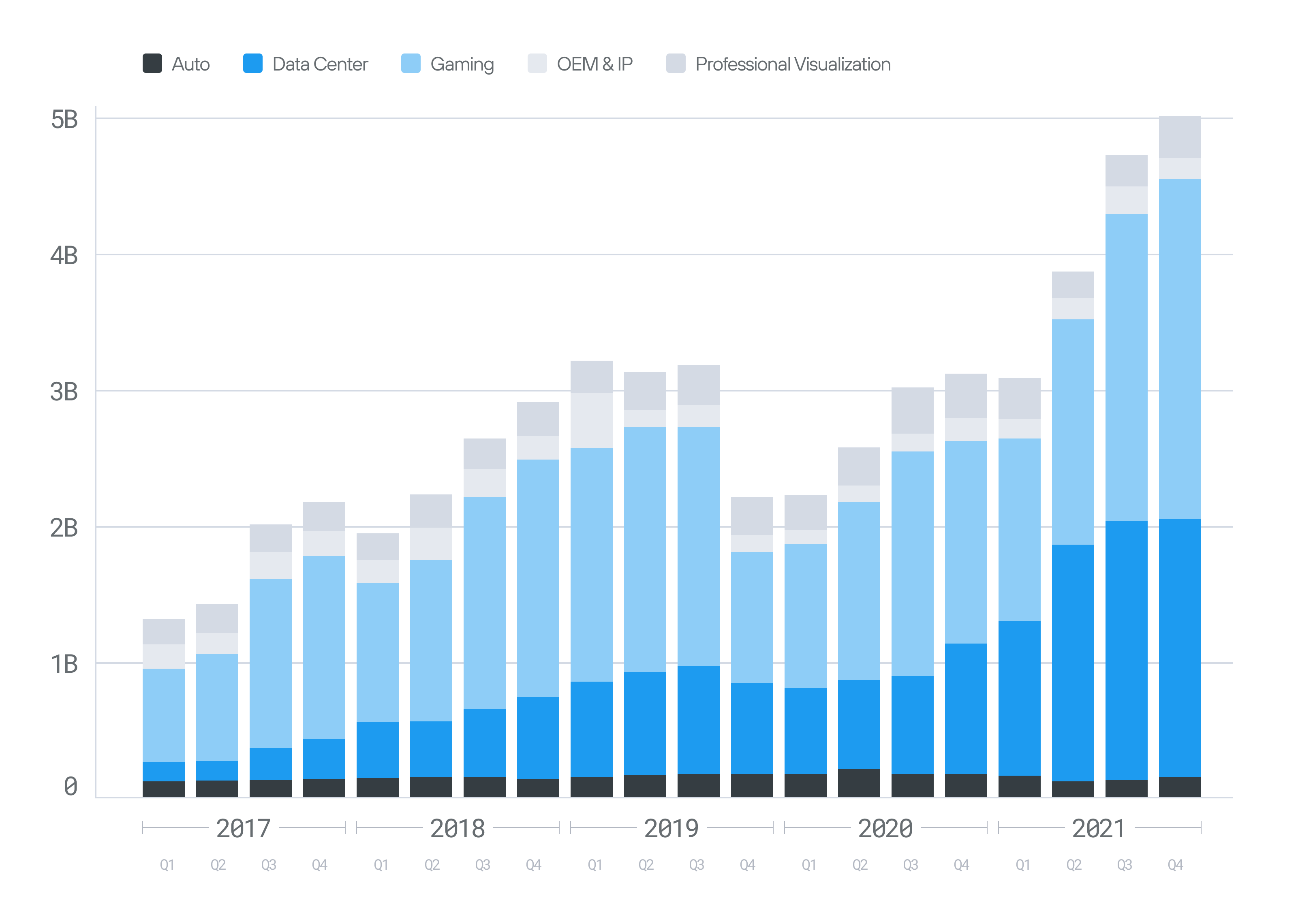

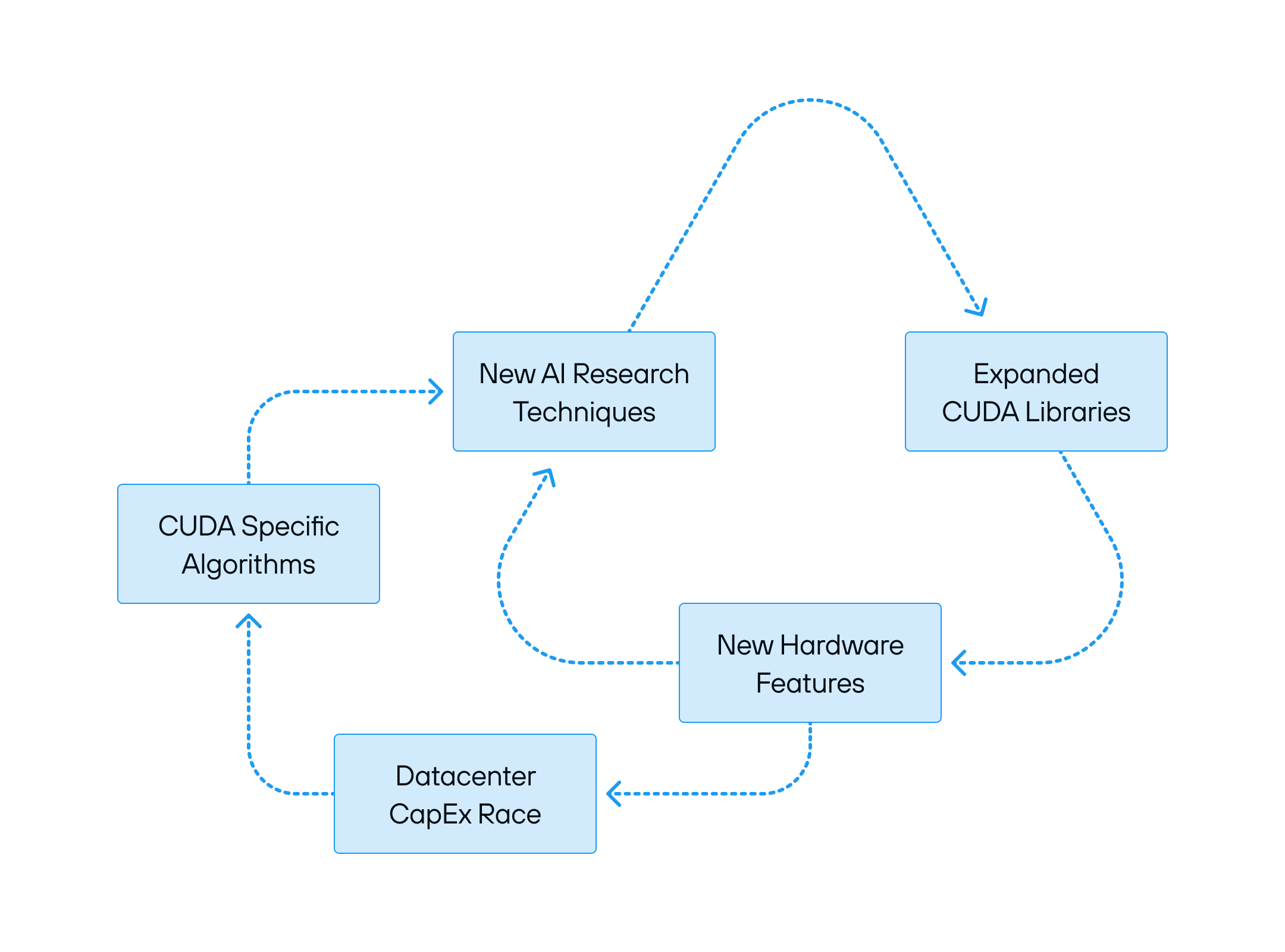

Almost overnight, demand for AI compute skyrocketed—it became the foundation for billion-dollar industries, consumer applications, and competitive corporate strategy. Big tech and venture capital firms poured billions into AI research startups and CapEx buildouts—money that ultimately funneled straight to NVIDIA, the only player capable of meeting the exploding demand for compute.

As demand for AI compute surged, companies faced a stark reality: training and deploying GenAI models is incredibly expensive. Every efficiency gain—no matter how small—translated into massive savings at scale. With NVIDIA’s hardware already entrenched in data centers, AI companies faced a serious choice: optimize for CUDA or fall behind. Almost overnight, the industry pivoted to writing CUDA-specific code. The result? AI breakthroughs are no longer driven purely by models and algorithms—they now hinge on the ability to extract every last drop of efficiency from CUDA-optimized code.

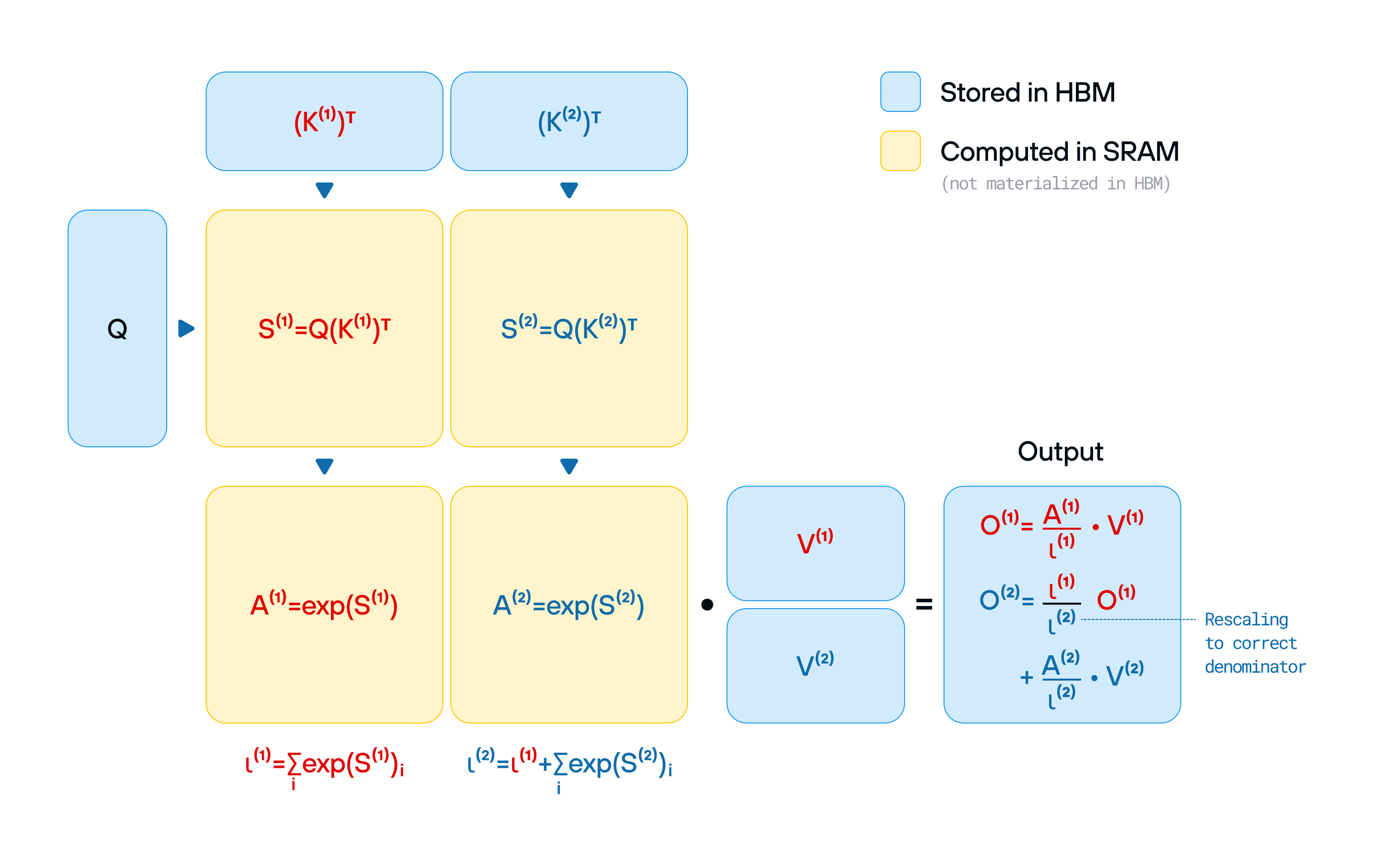

Take FlashAttention-3, for example: this cutting-edge optimization slashed the cost of running transformer models—but it was built exclusively for Hopper GPUs, reinforcing NVIDIA’s lock-in by ensuring the best performance was only available on its latest hardware. Continuous research innovations followed the same trajectory, for example when DeepSeek went directly to PTX assembly, gaining full control over the hardware at the lowest possible level. With the new NVIDIA Blackwell architecture on the horizon, we can look forward to the industry rewriting everything from scratch again.

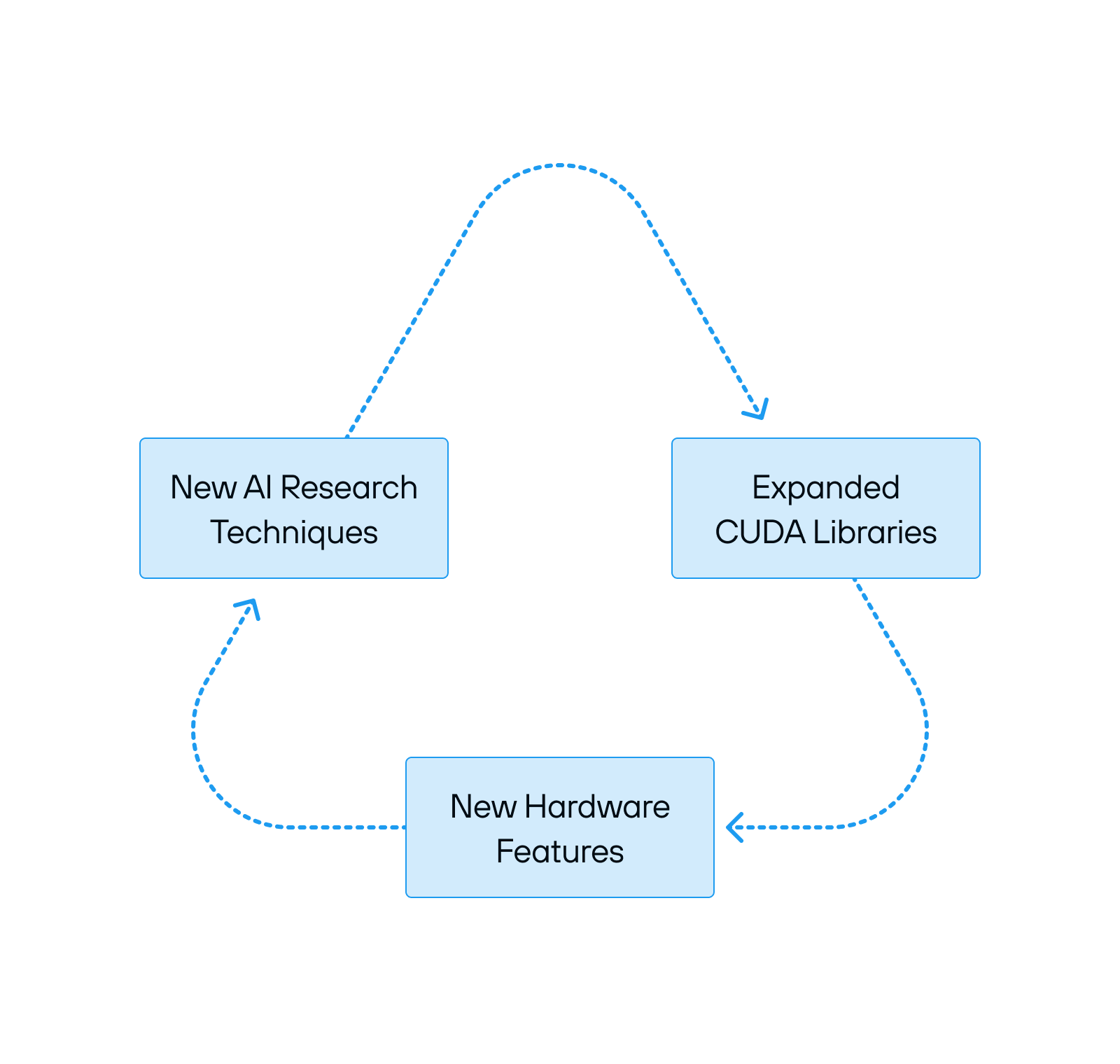

The Reinforcing Cycles That Power CUDA’s Grip

This system is accelerating and self-reinforcing. Generative AI has become a runaway force, driving an insatiable demand for compute, and NVIDIA holds all the cards. The biggest install base ensures that most AI research happens in CUDA, which in turn drives investment into optimizing NVIDIA’s platform.

Every new generation of NVIDIA hardware brings new features and new efficiencies, but it also demands new software rewrites, new optimizations, and deeper reliance on NVIDIA’s stack. The future seems inevitable: a world where CUDA’s grip on AI compute only tightens.

Except CUDA isn’t perfect.

The same forces that entrench CUDA’s dominance are also becoming a bottleneck—technical challenges, inefficiencies, and barriers to broader innovation. Does this dominance actually serve the AI research community? Is CUDA good for developers, or just good for NVIDIA?

Let’s take a step back: We looked at what CUDA is and why it is so successful, but is it actually good? We’ll explore this in Part 4—stay tuned and let us know if you find this series useful, or have suggestions/requests! 🚀

Democratizing AI Compute, Part 4: CUDA is the incumbent, but is it any good?

Answering the question of whether CUDA is “good” is much trickier than it sounds. Are we talking about its raw performance? Its feature set? Perhaps its broader implications in the world of AI development? Whether CUDA is “good” depends on who you ask and what they need. In this post, we’ll evaluate CUDA from the perspective of the people who use it day-in and day-out—those who work in the GenAI ecosystem:

- For AI engineers who build on top of CUDA, it’s an essential tool, but one that comes with versioning headaches, opaque driver behavior, and deep platform dependence.

- For AI engineers who write GPU code for NVIDIA hardware, CUDA offers powerful optimization but only by accepting the pain necessary to achieve top performance.

- For those who want their AI workloads to run on GPU’s from multiple vendors, CUDA is more an obstacle than a solution.

- Then there’s NVIDIA itself—the company that has built its fortune around CUDA, driving massive profits and reinforcing their dominance over AI compute.

So, is CUDA “good?” Let’s dive into each perspective to find out! 🤿

AI Engineers

Many engineers today are building applications on top of AI frameworks—agentic libraries like LlamaIndex, LangChain, and AutoGen—without needing to dive deep into the underlying hardware details. For these engineers, CUDA is a powerful ally. Its maturity and dominance in the industry bring significant advantages: most AI libraries are designed to work seamlessly with NVIDIA hardware, and the collective focus on a single platform fosters industry-wide collaboration.

However, CUDA’s dominance comes with its own set of persistent challenges. One of the biggest hurdles is the complexity of managing different CUDA versions, which can be a nightmare. This frustration is the subject of numerous memes:

Credit: x.com/ordax

This isn’t just a meme—it’s a real, lived experience for many engineers. These AI practitioners constantly need to ensure compatibility between the CUDA toolkit, NVIDIA drivers, and AI frameworks. Mismatches can cause frustrating build failures or runtime errors, as countless developers have experienced firsthand:

“I failed to build the system with the latest NVIDIA PyTorch docker image. The reason is PyTorch installed by pip is built with CUDA 11.7 while the container uses CUDA 12.1.” (github.com)

or:

“Navigating Nvidia GPU drivers and CUDA development software can be challenging. Upgrading CUDA versions or updating the Linux system may lead to issues such as GPU driver corruption.” (dev.to)

Sadly, such headaches are not uncommon. Fixing them often requires deep expertise and time-consuming troubleshooting. NVIDIA’s reliance on opaque tools and convoluted setup processes deters newcomers and slows down innovation.

In response to these challenges, NVIDIA has historically moved up the stack to solve individual point-solutions rather than fixing the fundamental problem: the CUDA layer itself. For example, it recently introduced NIM (NVIDIA Inference Microservices), a suite of containerized microservices aimed at simplifying AI model deployment. While this might streamline one use-case, NIM also abstracts away underlying operations, increasing lock-in and limiting access to the low-level optimization and innovation key to CUDA’s value proposition.

While AI engineers building on top of CUDA face challenges with compatibility and deployment, those working closer to the metal—AI model developers and performance engineers—grapple with an entirely different set of trade-offs.

AI Model Developers and Performance Engineers

For researchers and engineers pushing the limits of AI models, CUDA is simultaneously an essential tool and a frustrating limitation. For them, CUDA isn’t an API; it’s the foundation for every performance-critical operation they write. These are engineers working at the lowest levels of optimization, writing custom CUDA kernels, tuning memory access patterns, and squeezing every last bit of performance from NVIDIA hardware. The scale and cost of GenAI demand it. But does CUDA empower them, or does it limit their ability to innovate?

Despite its dominance, CUDA is showing its age. It was designed in 2007, long before deep learning—let alone GenAI. Since then, GPUs have evolved dramatically, with Tensor Cores and sparsity features becoming central to AI acceleration. CUDA’s early contribution was to make GPU programming easy, but it hasn’t evolved with modern GPU features necessary for transformers and GenAI performance. This forces engineers to work around its limitations just to get the performance their workloads demand.

CUDA doesn’t do everything modern GPUs can do

Cutting-edge techniques like FlashAttention-3 (example code) and DeepSeek’s innovations require developers to drop below CUDA into PTX—NVIDIA’s lower-level assembly language. PTX is only partially documented, constantly shifting between hardware generations, and effectively a black box for developers.

More problematic, PTX is even more locked to NVIDIA than CUDA, and its usability is even worse. However, for teams chasing cutting-edge performance, there’s no alternative—they’re forced to bypass CUDA and endure significant pain.

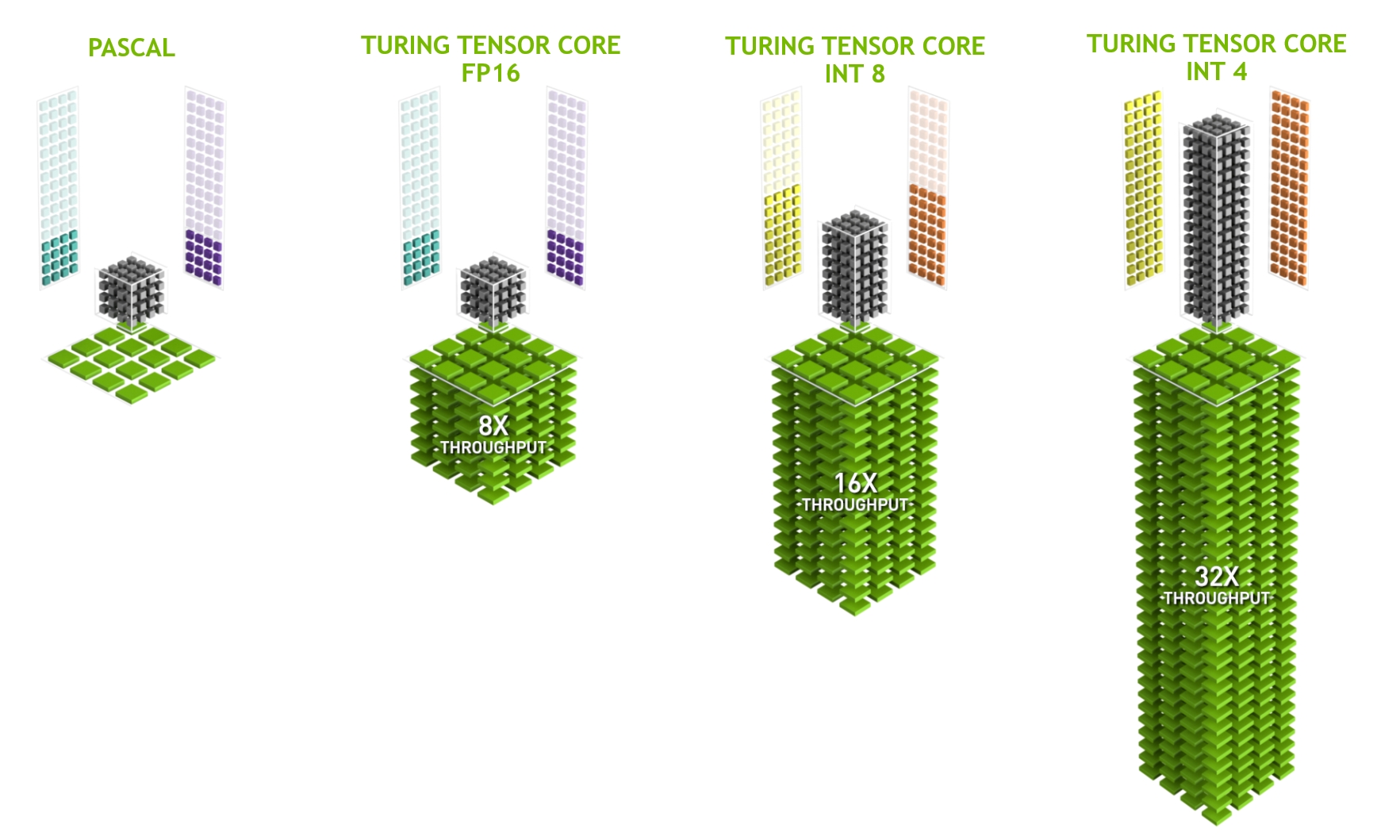

Tensor Cores: Required for performance, but hidden behind black magic

Today, the bulk of an AI model’s FLOPs come from “Tensor Cores”, not traditional CUDA cores. However, programming Tensor Cores directly is no small feat. While NVIDIA provides some abstractions (like cuBLAS and CUTLASS), getting the most out of GPUs still requires arcane knowledge, trial-and-error testing, and often, reverse engineering undocumented behavior. With each new GPU generation, Tensor Cores change, yet the documentation is dated. This leaves engineers with limited resources to fully unlock the hardware’s potential.

Credit: NVIDIA

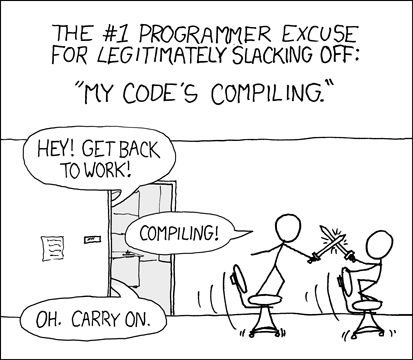

AI is Python, but CUDA is C++

Another major limitation is that writing CUDA fundamentally requires using C++, while modern AI development is overwhelmingly done in Python. Engineers working on AI models and performance in PyTorch don’t want to switch back and forth between Python and C++—the two languages have very different mindsets. This mismatch slows down iteration, creates unnecessary friction, and forces AI engineers to think about low-level performance details when they should be focusing on model improvements. Additionally, CUDA’s reliance on C++ templates leads to painfully slow compile times and often incomprehensible error messages.

Credit: XKCD

These are the challenges you face if you’re happy to develop specifically for NVIDIA hardware. But what if you care about more than just NVIDIA?

Engineers and Researchers Building Portable Software

Not everyone is happy to build software locked to NVIDIA’s hardware, and the challenges are clear. CUDA doesn’t run on hardware from other vendors (like the supercomputer in our pockets), and no alternatives provide the full performance and capabilities CUDA provides on NVIDIA hardware. This forces developers to write their AI code multiple times, for multiple platforms.

In practice, many cross-platform AI efforts struggle. Early versions of TensorFlow and PyTorch had OpenCL backends, but they lagged far behind the CUDA backend in both features and speed, leading most users to stick with NVIDIA. Maintaining multiple code paths—CUDA for NVIDIA, something else for other platforms—is costly, and as AI rapidly progresses, only large organizations have resources for such efforts.

The bifurcation CUDA causes creates a self-reinforcing cycle: since NVIDIA has the largest user base and the most powerful hardware, most developers target CUDA first, and hope that others will eventually catch up. This further solidifies CUDA’s dominance as the default platform for AI.

👉 We’ll explore alternatives like OpenCL, TritonLang, and MLIR compilers in our next post, and come to understand why these options haven’t made a dent in CUDA’s dominance.

Is CUDA Good for NVIDIA Itself?

Of course, the answer is yes: the “CUDA moat” enables a winner-takes-most scenario. By 2023, NVIDIA held ~98% of the data-center GPU market share, cementing its dominance in the AI space. As we’ve discussed in previous posts, CUDA serves as the bridge between NVIDIA’s past and future products, driving the adoption of new architectures like Blackwell and maintaining NVIDIA’s leadership in AI compute.

However, legendary hardware experts like Jim Keller argue that “CUDA’s a swamp, not a moat,” making analogies to the X86 architecture that bogged Intel down.

“CUDA’s a swamp, not a moat,” argues Jim Keller

How could CUDA be a problem for NVIDIA? There are several challenges.

CUDA’s usability impacts NVIDIA the most

Jensen Huang famously claims that NVIDIA employs more software engineers than hardware engineers, with a significant portion dedicated to writing CUDA. But the usability and scalability challenges within CUDA slow down innovation, forcing NVIDIA to aggressively hire engineers to fire-fight these issues.

CUDA’s heft slows new hardware rollout

CUDA doesn’t provide performance portability across NVIDIA’s own hardware generations, and the sheer scale of its libraries is a double-edged sword. When launching a new GPU generation like Blackwell, NVIDIA faces a choice: rewrite CUDA or release hardware that doesn’t fully unleash the new architecture’s performance. This explains why performance is suboptimal at launch of each new generation. Such expansion of CUDA’s surface area is costly and time-consuming.

The Innovator’s Dilemma

NVIDIA’s commitment to backward compatibility—one of CUDA’s early selling points—has now become “technical debt” that hinders their own ability to innovate rapidly. While maintaining support for older generations of GPUs is essential for their developer base, it forces NVIDIA to prioritize stability over revolutionary changes. This long-term support costs time, resources, and could limit their flexibility moving forward.

Though NVIDIA has promised developers continuity, Blackwell couldn’t achieve its performance goals without breaking compatibility with Hopper PTX—now some Hopper PTX operations don’t work on Blackwell. This means advanced developers who have bypassed CUDA in favor of PTX may find themselves rewriting their code for the next-generation hardware.

Despite these challenges, NVIDIA’s strong execution in software and its early strategic decisions have positioned them well for future growth. With the rise of GenAI and a growing ecosystem built on CUDA, NVIDIA is poised to remain at the forefront of AI compute and has rapidly grown into one of the most valuable companies in the world.

Where Are the Alternatives to CUDA?

In conclusion, CUDA remains both a blessing and a burden, depending on which side of the ecosystem you’re on. Its massive success drove NVIDIA’s dominance, but its complexity, technical debt, and vendor lock-in present significant challenges for developers and the future of AI compute.

With AI hardware evolving rapidly, a natural question emerges: Where are the alternatives to CUDA? Why hasn’t another approach solved these issues already? In Part 5, we’ll explore the most prominent alternatives, examining the technical and strategic problems that prevent them from breaking through the CUDA moat. 🚀

Democratizing AI Compute, Part 5: What about OpenCL and CUDA C++ alternatives?

GenAI may be new, but GPUs aren’t! Over the years, many have tried to create portable GPU programming models using C++, from OpenCL to SYCL to OneAPI and beyond. These were the most plausible CUDA alternatives that aimed to democratize AI compute, but you may have never heard of them - because they failed to be relevant for AI.

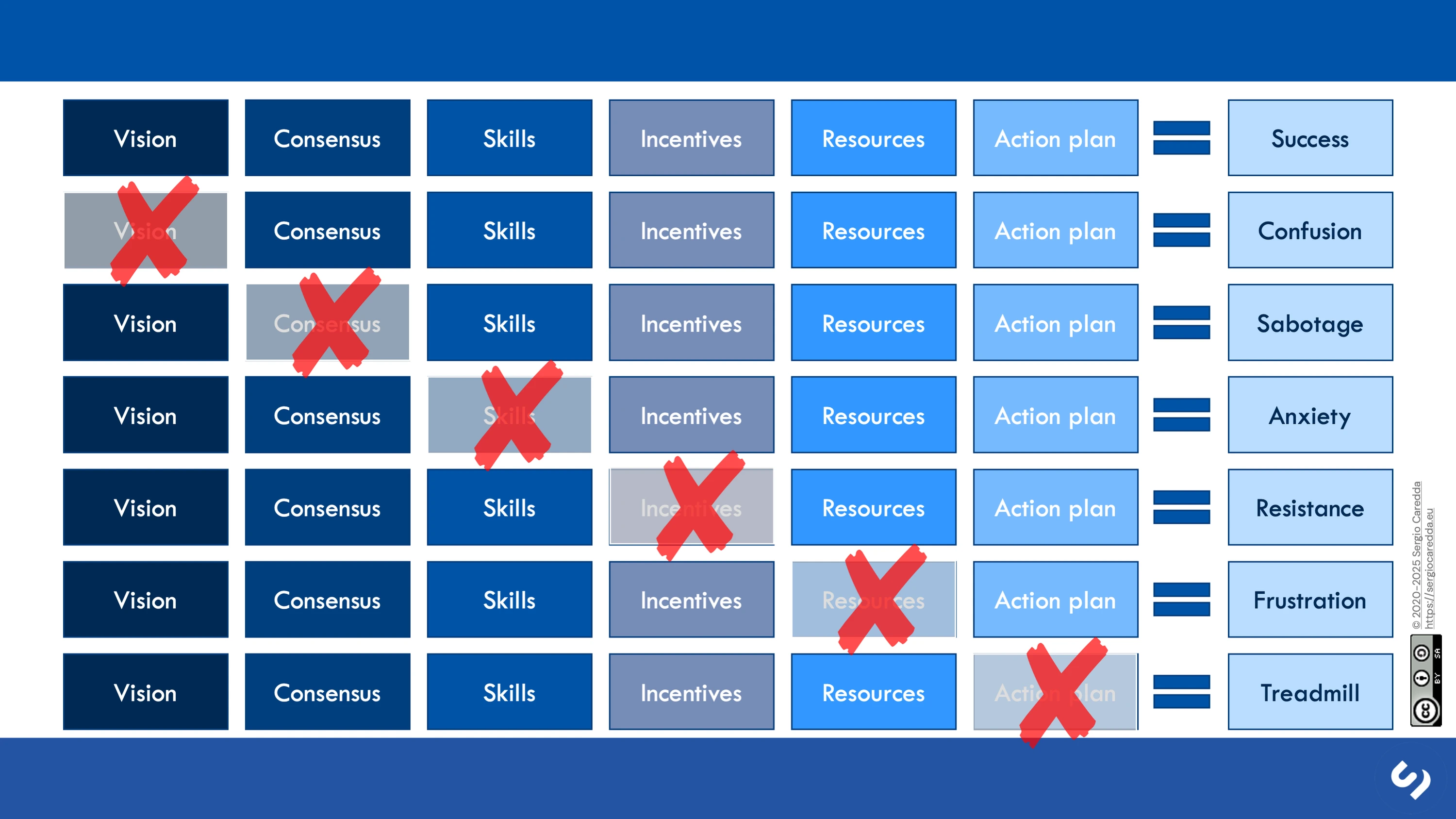

These projects have all contributed meaningfully to compute, but if we are serious about unlocking AI compute for the future, we must critically examine the mistakes that held them back—not just celebrate the wins. At a high level, the problems stem from the challenges of “open coopetition“—where industry players both collaborate and compete—as well as specific management missteps along the way.

Let’s dive in. 🚀

CUDA C++ Alternatives: OpenCL, SYCL, and More

There are many projects that aimed to unlock GPU programming, but the one I know best is OpenCL. Like CUDA, OpenCL aimed to give programmers a C++-like experience for writing code that ran on the GPU. The history is personal: in 2008, I was one of the lead engineers implementing OpenCL at Apple (it was the first production use of the Clang compiler I was building). After we shipped it, we made the pivotal decision to contribute it to the Khronos Group so it could get adopted and standardized across the industry.

That decision led to broad industry adoption of OpenCL (see the logos), particularly in mobile and embedded devices. Today, it remains hugely successful, powering GPU compute on platforms like Android, as well as in specialized applications such as DSPs. Unlike CUDA, OpenCL was designed for portability from the outset, aiming to support heterogeneous compute across CPUs, GPUs, and other accelerators. OpenCL also inspired other systems like SyCL, Vulkan, SPIR-V, oneAPI, WebCL and many others.

However, despite its technical strengths and broad adoption, OpenCL never became the dominant AI compute platform. There are several major reasons for this: the inherent tensions of open coopetition, technical problems that flowed from that, the evolving requirements of AI, and NVIDIA’s unified strategy with TensorFlow and PyTorch.

“Coopetition” at Committee Speed

In 2008, Apple was a small player in the PC space, and thought that industry standardization would enable it to reach more developers. However, while OpenCL did gain broad adoption among hardware makers, its evolution quickly ran into a major obstacle: the speed of committee-driven development. For Apple, this slow-moving, consensus-driven process was a dealbreaker: we wanted to move the platform rapidly, add new features (e.g. add C++ templates), and express the differentiation of the Apple platform. We faced a stark reality - the downside of a committee standard is that things suddenly moved at committee consensus speed… which felt glacial.

Hardware vendors recognized the long-term benefits of a unified software ecosystem, but in the short term, they were fierce competitors. This led to subtle but significant problems: instead of telling the committee about the hardware features you’re working on (giving a competitor a head start), participants would keep innovations secret until after the hardware shipped, and only discuss it after these features became commoditized (using vendor-specific extensions instead).

Coopetition: “cooperation” amongst competitors

This became a huge problem for Apple, a company that wanted to move fast in secret to make a big splash with product launches. As such, Apple decided to abandon OpenCL: it introduced Metal instead, never brought OpenCL to iOS, and deprecated it out of macOS later. Other companies stuck with OpenCL, but these structural challenges continued to limit its ability to evolve at the pace of cutting-edge AI and GPU innovation.

Technical Problems with OpenCL

While Apple boldly decided to contribute the OpenCL standard to Kronos, it wasn’t all-in: it contributed OpenCL as a technical specification—but without a full reference implementation. Though parts of the compiler front-end (Clang) was open source, there was no shared OpenCL runtime, forcing vendors to develop their own custom forks and complete the compiler. Each vendor had to maintain its own implementation (a ”fork”), and without a shared, evolving reference, OpenCL became a patchwork of vendor-specific forks and extensions. This fragmentation ultimately weakened its portability—the very thing it was designed to enable.

Furthermore, because vendors held back differentiated features or isolated them into vendor-specific extensions, which exploded in number and fragmented OpenCL (and the derivatives), eroding its ability to be a unifying vendor-agnostic platform. These problems were exacerbated by weaknesses in OpenCL’s compatibility and conformance tests. On top of that, it inherited all the “C++ problems” that we discussed before.

Developers want stable, well-supported tools—but OpenCL’s fragmentation, weak conformance tests, and inconsistent vendor support made it an exercise in frustration. One developer summed it up by saying that using OpenCL is “about as comfortable as hugging a cactus”! Ouch.

One developer described using OpenCL as “about as comfortable as hugging a cactus.”

While OpenCL was struggling with fragmentation and slow committee-driven evolution, AI was rapidly advancing—both in software frameworks and hardware capabilities. This created an even bigger gap between what OpenCL offered and what modern AI workloads needed.

The Evolving Needs of AI Research and AI GPU Hardware

The introduction of TensorFlow and PyTorch kicked off a revolution in AI research - powered by improved infrastructure and massive influx of BigCo funding. This posed a major challenge for OpenCL. While it enabled GPU compute, it lacked the high-level AI libraries and optimizations necessary for training and inference at scale. Unlike CUDA, it had no built-in support for key operations like matrix multiplication, Flash Attention, or datacenter-scale training.

Cross-industry efforts to expand TensorFlow and PyTorch to use OpenCL quickly ran into fundamental roadblocks (despite being obvious and with incredible demand). The developers who kept hugging the cactus soon discovered a harsh reality: portability to new hardware is meaningless if you can’t unlock its full performance. Without a way to express portable hardware-specific enhancements—and with coopetition crushing collaboration—progress stalled.

One glaring example? OpenCL still doesn’t provide standardized support for Tensor Cores—the specialized hardware units that power efficient matrix multiplications in modern GPUs and AI accelerators. This means that using OpenCL often means a 5x to 10x slowdown in performance compared to using CUDA or other fragmented vendor native software. For GenAI, where compute costs are already astronomical, a 5x to 10x slowdown isn’t just inconvenient—it’s a complete dealbreaker.

NVIDIA’s Strategic Approach with TensorFlow and PyTorch

While OpenCL struggled under the weight of fragmented governance, NVIDIA took a radically different approach—one that was tightly controlled, highly strategic, and ruthlessly effective, as we discussed earlier. It actively co-designed CUDA’s high-level libraries alongside TensorFlow and PyTorch, ensuring they always ran best on NVIDIA hardware. Since these frameworks were natively built on CUDA, NVIDIA had a massive head start—and it doubled down by optimizing performance out of the box.

NVIDIA maintained a token OpenCL implementation—but it was strategically hobbled (e.g., not being able to use TensorCores)—ensuring that a CUDA implementation would always be necessary. NVIDIA’s continued and rising dominance in the industry put it on the path to ensure that the CUDA implementations would always be the most heavily invested in. Over time, OpenCL support faded, then vanished—while CUDA cemented its position as the undisputed standard.

What Can We Learn From These C++ GPU Projects?

The history above is well understood by those of us who lived through it, but the real value comes from learning from the past. Based on this, I believe successful systems must:

- Provide a reference implementation, not just a paper specification and “compatibility” tests. A working, adoptable, and scalable implementation should define compatibility—not a PDF.

- Have strong leadership and vision driven by whoever maintains the reference implementation.

- Run with top performance on the industry leader’s hardware—otherwise, it will always be a second-class alternative, not something that can unify the industry.

- Evolve rapidly to meet changing requirements, because AI research isn’t stagnant, and AI hardware innovation is still accelerating.

- Cultivate developer love, by providing great usability, tools and fast compile times. Also, “C++ like” isn’t exactly a selling point in AI!

- Build an open community, because without widespread adoption, technical prowess doesn’t matter.

- Avoid fragmentation—a standard that splinters into incompatible forks can’t provide an effective unification layer for software developers.

These are the fundamental reasons why I don’t believe that committee efforts like OpenCL can ever succeed. It’s also why I’m even more skeptical of projects like Intel’s OneAPI (now UXL Foundation) that are notionally open, but in practice, controlled by a single hardware vendor competing with all the others.

What About AI Compilers?

At the same time that C++ approaches failed to unify AI compute for hardware makers, the AI industry faced a bigger challenge—even using CUDA on NVIDIA hardware. How can we scale AI compute if humans have to write all the code manually? There are too many chips, too many AI algorithms, and too many workload permutations to optimize by hand.

As AI’s dominance grew, it inevitably attracted interest from systems developers and compiler engineers—including myself. In the next post, we’ll dive into widely known “AI compiler” stacks like TVM, OpenXLA, and MLIR—examining what worked, what didn’t, and what lessons we can take forward. Unfortunately, the lessons are not wildly different than the ones above:

History may not repeat itself, but it does rhyme. - Mark Twain

See you next time—until then, may the FLOPS be with you! 👨💻

Democratizing AI Compute, Part 6: What about AI compilers (TVM and XLA)?

In the early days of AI hardware, writing high-performance GPU code was a manageable—if tedious—task. Engineers could handcraft CUDA kernels in C++ for the key operations they needed, and NVIDIA could build these into libraries like cuDNN to drive their lock-in. But as deep learning advanced, this approach completely broke down.

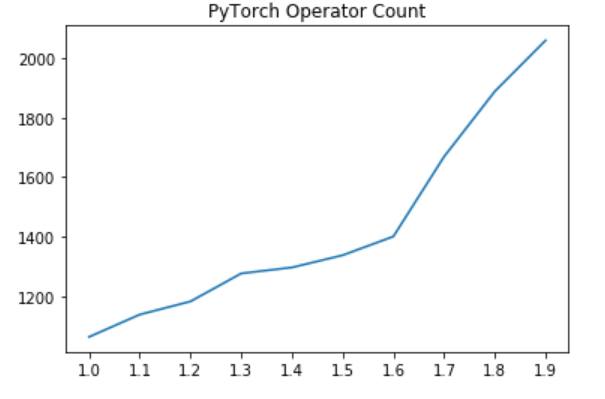

Neural networks grew bigger, architectures became more sophisticated, and researchers demanded ever-faster iteration cycles. The number of unique operators in frameworks like PyTorch exploded—now numbering in the thousands. Manually writing and optimizing each one for every new hardware target? Impossible.

PyTorch operator count by version (source)

This challenge forced a fundamental shift: instead of writing kernels by hand, what if we had a compiler that could generate them automatically? AI compilers emerged to solve this exact problem, marking a transformation from human-crafted CUDA to machine-generated, hardware-optimized compute.

But as history has shown, building a successful compiler stack isn’t just a technical challenge—it’s a battle over ecosystems, fragmentation, and control. So what worked? What didn’t? And what can we learn from projects like TVM and OpenXLA?

Let’s dive in. 🚀

What is an “AI Compiler”?

At its core, an AI compiler is a system that takes high-level operations—like those in PyTorch or TensorFlow—and automatically transforms them into highly efficient GPU code. One of the most fundamental optimizations it performs is called “kernel fusion.” To see why this matters, let’s consider a simple example: multiplying two matrices (”matmul”) and then applying a ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) activation function. These are simple but important operations that occur in common neural networks.

Naïve approach: Two separate kernels

The most straightforward (but inefficient) way to do this is to perform matrix multiplication first, store the result in memory, then load it again to apply ReLU.

# Naïve matmul implementation for clarity.

def matmul(A, B):

# Initialize result matrix to zero.

C = [[0] * N for _ in range(N)]

for i in range(N):

for j in range(N):

sum = 0

for k in range(N):

# Matmul sums the dot product of rows and columns.

sum += A[i][k] * B[k][j]

C[i][j] = sum # store one output value

return C

# ReLU clamp negatives to zero with the "max" function.

def relu(C):

# Allocate result array.

result = [[0] * N for _ in range(N)]

for i in range(N):

for j in range(N):

# This loads from memory, does a trivial max(0, x) operation,

# then stores the result.

result[i][j] = max(0, C[i][j])

return result

C = matmul(A, B) # Compute matrix multiplication first

D = relu(C) # Then apply ReLU separately.

These operations are extremely familiar to engineers that might write a CUDA kernel (though remember that CUDA uses unwieldy C++ syntax!), and there are many tricks used for efficient implementation.

While the above approach is simple and modular, executing operations like this is extremely slow because it writes the entire matrix C to memory after matmul(), then reads it back again in relu(). This memory traffic dominates performance, especially on GPUs, where memory access is more expensive than local compute.

Fused kernel: One pass, no extra memory traffic

The solution for this is simple: we can “fuse” these two operations into a single kernel, eliminating redundant memory access. Instead of storing C after matmul(), we apply relu() immediately inside the same loop:

# Fused kernel: Matrix multiplication + ReLU in one pass

def fused_matmul_relu(A, B):

# Initialize result matrix to zero.

C = [[0] * N for _ in range(N)]

for i in range(N):

for j in range(N):

sum = 0

for k in range(N):

sum += A[i][k] * B[k][j] # Compute matmul

# Apply ReLU in the same loop!

C[i][j] = max(0, sum)

return C # Only one read/write cycle

# Compute in a single pass, no extra memory.

C = fused_matmul_relu(A, B)

While the benefit of this transformation varies by hardware and matrix size, the results can be profound: sometimes 2x better performance! Why is this the case? By fusing the operations:

-

✅ We eliminate an extra memory write/read, reducing pressure on memory bandwidth.

-

✅ We keep data in registers or shared memory, avoiding slow global memory access.

-

✅ We reduce memory usage and allocation/deallocation overhead, since the intermediate buffer has been removed.

This is the simplest example of kernel fusion: There are many more powerful transformations, and AI kernel engineers have always pushed the limits of optimization (learn more). With GenAI driving up compute demand, these optimizations are more critical than ever.

Great performance, but an exponential complexity explosion!

While these sorts of optimizations can be extremely exciting and fun to implement for those who are chasing low cost and state of the art performance, there is a hidden truth: this approach doesn’t scale.

Modern machine learning toolkits include hundreds of different “operations” like matmul, convolution, add, subtract, divide, etc., as well as dozens of activation functions beyond ReLU. Each neural network needs them to be combined in different ways: this causes an explosion in the number of permutations that need to be implemented (hundreds of operations x hundreds of operations = too many to count). NVIDIA’s libraries like cuDNN provide a fixed list of options to choose from, without generality to new research.

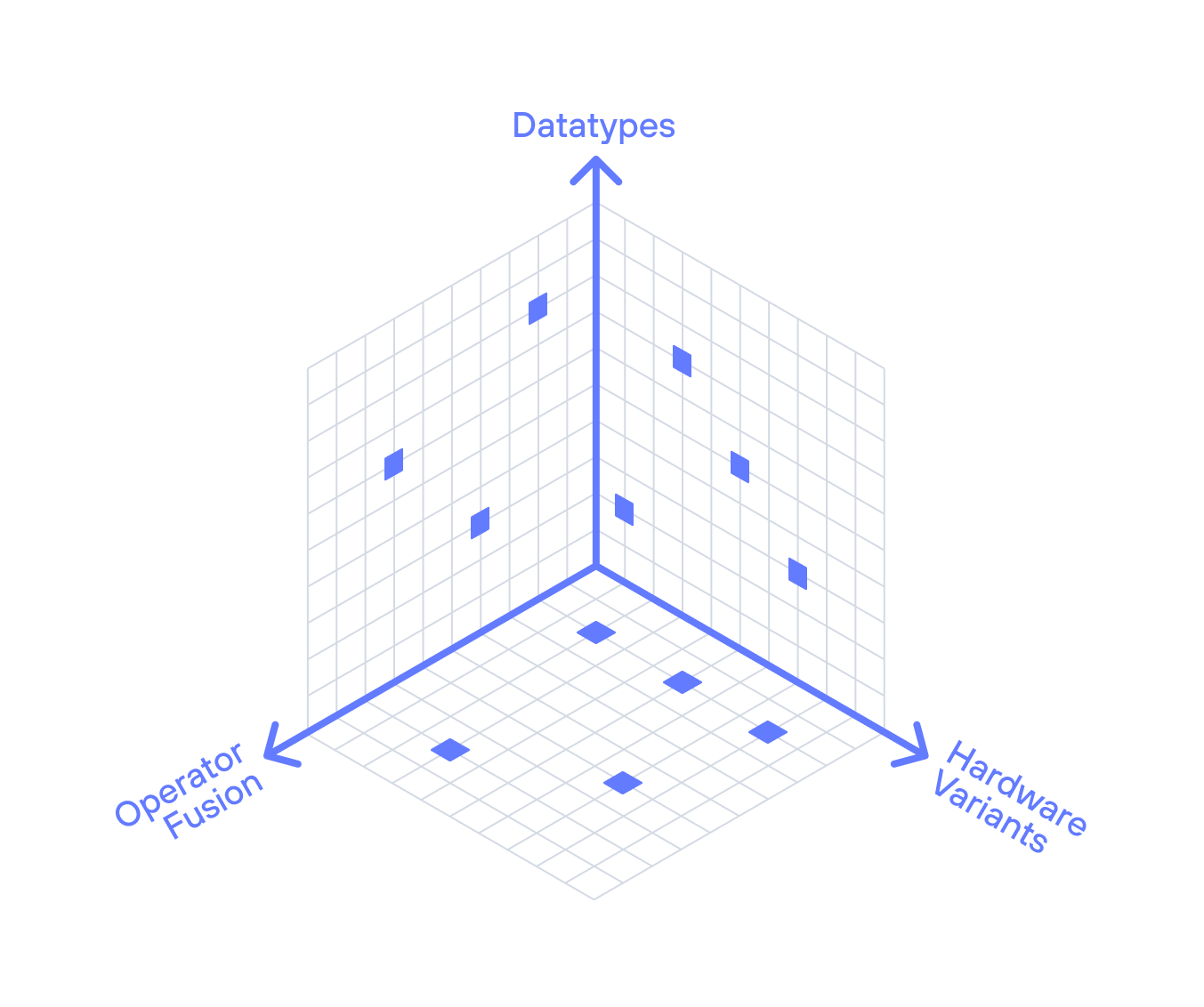

Furthermore, there are other axes of explosion as well: we’ve seen an explosion of new numerics datatypes (e.g. “float8”), and of course, there is also an explosion of the kind of hardware that AI should support.

Just three dimensions of complexity

Early AI compilers: TVM

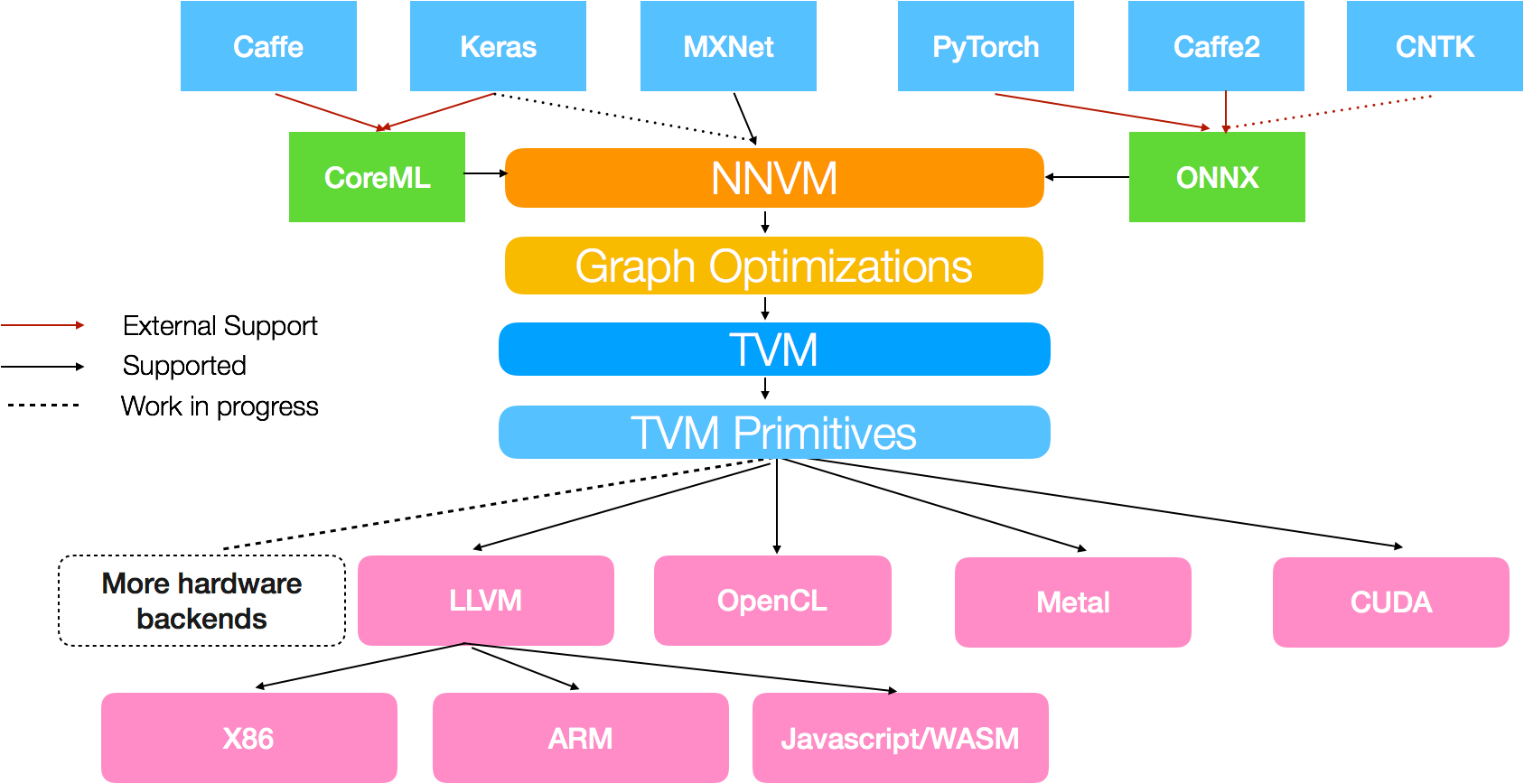

There are many AI compilers, but one of the earliest and most successful is TVM - the “Tensor Virtual Machine”. This system took models from TensorFlow/PyTorch and optimized them for diverse hardware, i.e. by applying kernel fusion automatically. This project started at the University of Washington by Tianqi Chen and Professor Luis Ceze in about 2016, and delivered a number of innovative results and performance wins described in the 2018 paper that outlines the TVM architecture. It was open sourced and incorporated into the Apache project.

Across its journey, TVM has been adopted by hardware makers (including public contributions from companies like ARM, Qualcomm, Facebook, Intel, and many others) across embedded, DSP, and many other applications. TVM’s core contributors later founded OctoAI, which NVIDIA acquired in late 2024—giving it control over many of the original TVM developers and, potentially, the project’s future.

TVM is an important step for the AI compiler industry, but what can we learn from it? Here are my key takeaways. Disclaimer: although TVM was a user of LLVM and I had great interest in it, I was never directly involved. This is my perspective as an outsider.

Wasn’t able to deliver performance on modern hardware

TVM struggled to deliver peak performance on modern AI hardware, particularly as GPUs evolved toward TensorCores and other specialized acceleration. It added support over time but was often late and failed to fully unlock performance. As such, it suffered from one of the same problems as OpenCL: You can’t deliver performance if you can’t unlock the hardware.

Fragmentation driven by conflicting commercial interests

Unlike OpenCL, TVM wasn’t just a specification—it was an actual implementation. This made it far more useful out of the box and attracted hardware vendors. But fragmentation still reared its head: vendors forked the code, made incompatible changes, and struggled to stay in sync, slowing progress. This led to friction executing architectural changes (because downstream vendors complained about their forks being broken), which slowed development.

Agility is required to keep up with rapid AI advances

A final challenge is that TVM was quite early, but the pace of AI innovation around it was rapid. TensorFlow and PyTorch rapidly evolved due to backing by huge companies like Google, Meta, and NVIDIA, improving their performance and changing the baselines that TVM compared against. The final nail in the coffin, though, was GenAI, which changed the game. TVM was designed for “TradAI”: a set of relatively simple operators that needed fusion, but GenAI has large and complex algorithms deeply integrated with the hardware—things like FlashAttention3. TVM fell progressively behind as the industry evolved.

Less strategically important (but still material), TVM also has technical problems, e.g. really slow compile times due to excessive auto-tuning. All of these together contributed to project activity slowing.

Today, NVIDIA now employs many of its original leaders, leaving its future uncertain. Meanwhile, Google pursued its own vision with OpenXLA…

The XLA compiler from Google: Two different systems under one name

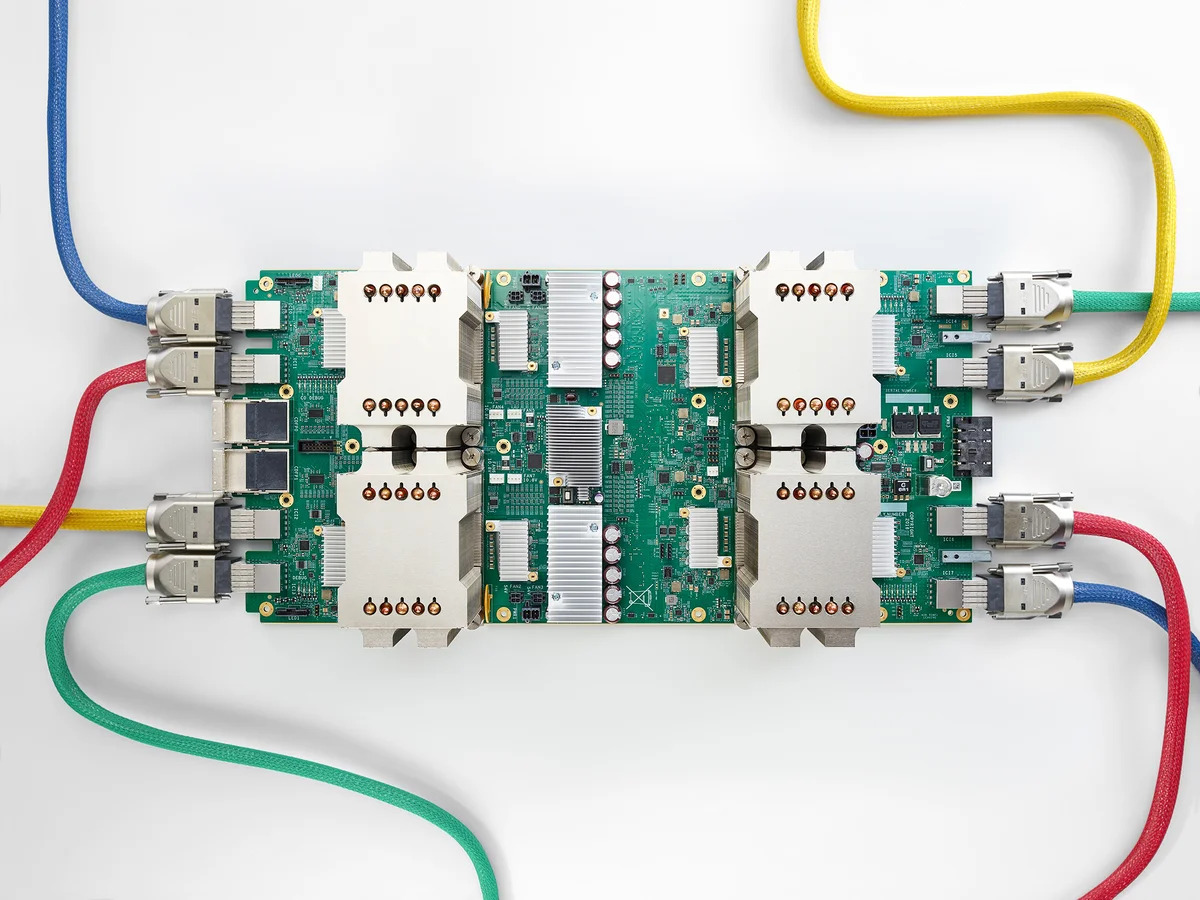

Unlike TVM, which started as an academic project, XLA was built within Google—one of the most advanced AI companies, with deep pockets and a vested interest in AI hardware. Google developed XLA to replace CUDA for its (now successful) TPU hardware, ensuring tight integration and peak performance for its own AI workloads. I joined Google Brain in 2017 to help scale TPUs (and XLA) from an experimental project into the world’s second-most successful AI accelerator (behind NVIDIA).

Google TPU (source)

Google had hundreds of engineers working on XLA (depending on how you count), and it evolved rapidly. Google added CPU and GPU support, and eventually formed the OpenXLA foundation. XLA is used as the AI compiler foundation for several important hardware projects, including AWS Inferentia/Trainium among others.

Beyond code generation, one of the biggest achievements and contributions of XLA is its ability to handle large scale machine learning models. At extreme scale, the ability to train with many thousands of chips becomes essential. Today, the largest practical models are starting to require advanced techniques to partition them across multiple machines—XLA developed clean and simple approaches that enable this.

Given all this investment, why don’t leading projects like PyTorch and vLLM run GPUs with XLA? The answer is that XLA is two different projects with a conflated brand, incentive structure challenges for their engineers, governance struggles, and technical problems that make it impractical.

Google uses XLA-TPU, but OpenXLA is for everyone else

The most important thing to understand is that XLA exists in two forms: 1) the internal, closed source XLA-TPU compiler that powers Google’s AI infrastructure, and 2) OpenXLA, the public project for CPUs and GPUs. These two share some code (“StableHLO”) but the vast majority of the code (and corresponding engineering effort) in XLA is Google TPU specific—closed and proprietary, and not used on CPUs or GPUs. XLA on GPU today typically calls into standard CUDA libraries to get performance. 🤷

This leads to significant incentive structure problems—Google engineers might want to build a great general-purpose AI compiler, but their paychecks are tied to making TPUs go brrr. Leadership has little incentive to optimize XLA for GPUs or alternative hardware—it’s all about keeping TPUs competitive. In my experience, XLA has never prioritized a design change that benefits other chips if it risks TPU performance.

The result? A compiler that works great for TPUs but falls short elsewhere.

Governance of OpenXLA

XLA was released early as an open source but explicitly Google-controlled project. Google’s early leadership in AI with TensorFlow got it adopted by other teams around the industry. In March 2023, the project was renamed to OpenXLA with an announcement about independence.

Despite this rebranding, Google still controls OpenXLA (seen in its governance structure), and doesn’t seem to be investing: there are declining community contributions, and the OpenXLA X account has been inactive since 2023.

Technical challenges with XLA

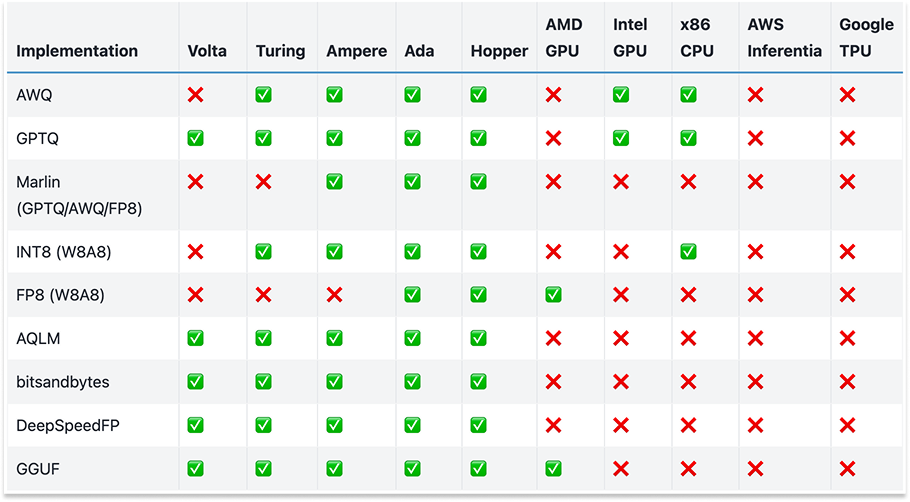

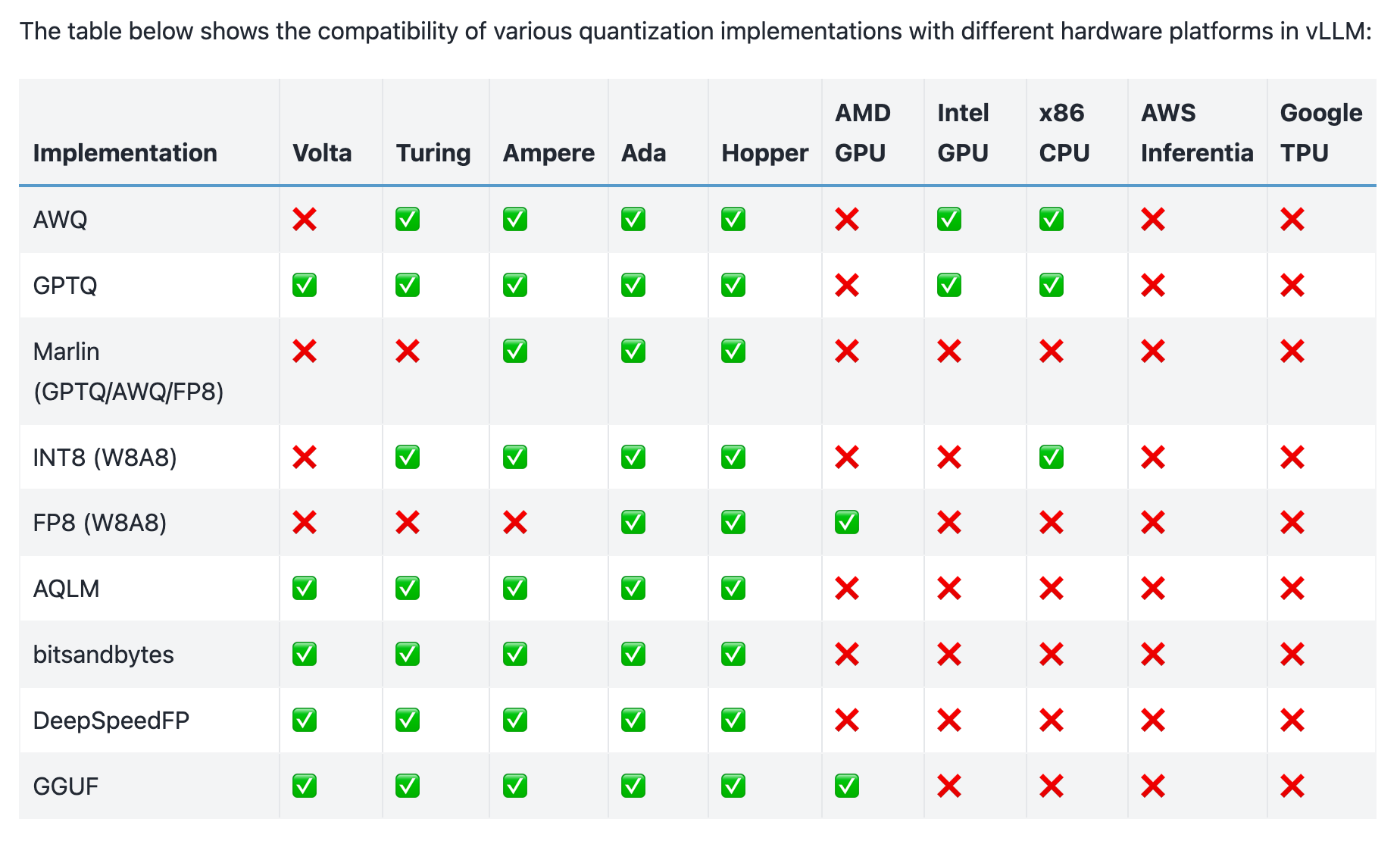

Like TVM, XLA was designed around a fixed set of predefined operators (StableHLO). This approach worked well for traditional AI models like ResNet-50 in 2017, but struggles with modern GenAI workloads, which require more flexibility in datatypes, custom kernels, and hardware-specific optimizations. This is a critical problem today, when modern GenAI algorithms require innovation in datatypes (see the chart below), or as DeepSeek showed us, at the hardware level and in novel communication strategies.

Datatypes supported in vLLM 0.7 by hardware type (source)

As a consequence, XLA (like TVM) suffers from being left behind by GenAI: today much of the critical workloads are written in experimental systems like Pallas that bypass the XLA compiler, even on TPUs. The core reason is that in its efforts to simplify AI compilation, XLA abstracted away too much of the hardware. This worked for early AI models, but GenAI demands fine-grained control over accelerators—something XLA simply wasn’t built to provide. And so, just like TVM, it’s being left behind.

Lessons learned from TVM and XLA

I take pride in the technical accomplishments we proved in XLA-TPU: XLA supported many generational research breakthroughs, including the invention of the transformer, countless model architectures, and research and product scaling that isn’t seen anywhere else. It is clearly the most successful non-NVIDIA training and inference hardware that exists, and powers Google’s (many) leading AI products and technologies. Though I know less about it, I have a lot of respect for TVM’s contribution to compiler research, autotuning and powering many early AI systems.

That said, there is a lot to learn from both projects together. Going down the list of lessons learned from OpenCL:

-

“Provide a reference implementation”: They both provide a useful implementation, not just a technical specification like OpenCL. 👍

-

“Have strong leadership and vision”: They have defined leadership teams and a vision behind them 👍. However, OpenXLA’s vision isn’t aligned with hardware teams that want to adopt it. And like many Google projects, its long-term prospects are uncertain, making it risky to depend on. 👎

-

“Run with top performance on the industry leader’s hardware”: Neither XLA nor TVM could fully unlock NVIDIA GPUs without calling into CUDA libraries, and thus it is unclear whether they are “good” on other AI accelerators without similar libraries to call into. 👎 XLA on TPUs does show the power of TPU hardware and its greater scalability than NVIDIA hardware. 👍

-

“Evolve rapidly”: Both projects were built for traditional deep learning, but GenAI shattered their assumptions. The shift to massive models, complex memory hierarchies, and novel attention mechanisms required a new level of hardware-software co-design that they weren’t equipped to handle. 👎 This ultimately made both projects a lot less interesting to folks who might want to use them on modern hardware that is expected to support GenAI. 👎👎

-

“Cultivate developer love”: In its strong spot, XLA provided a simple and clean model that people could understand, one that led to the rise of the JAX framework among others. 👍👍 TVM had cool technology but wasn’t a joy to use with long compile times and incompatibility with popular AI models. 👎

-

“Build an open community”: TVM built an open community, and OpenXLA aimed to. Both benefited from industry adoption as a result. 👍 “Avoid fragmentation”: Neither project did–TVM was widely forked and changed downstream, and XLA never accepted support for non-CPU/GPU hardware in its tree; all supported hardware was downstream. 👎

The pros and cons of AI compiler technology

First-generation AI frameworks like TensorFlow and PyTorch 1.0 relied heavily on hand-written CUDA kernels, which couldn’t scale to rapidly evolving AI workloads. TVM and XLA, as second-generation approaches, tackled this problem with automated compilation. However, in doing so, they sacrificed key strengths of the first generation: extensibility for custom algorithms, fine-grained control over hardware, and dynamic execution—features that turned out to be critical for GenAI.

Beyond what we learned from OpenCL, we can also add a few wishlist items:

-

Enable full programmability: We can’t democratize AI if we hide the power of any given chip from the developer. If you spend $100M on a cluster of one specific kind of GPU, you’ll want to unlock the full power of that silicon without being limited to a simplified interface.

-

Provide leverage over AI complexity: The major benefit of AI compilers is that it allows one to scale into the exponential complexity of AI (operators, datatypes, etc) without having to manually write a ton of code. This is essential to unlock next generation research.

-

Enable large scale applications: The transformative capability of XLA is the ability to easily scale to multiple accelerators and nodes. This capability is required to support the largest and most innovative models with ease. This is something that CUDA never really cracked.

Despite the wins and losses of these AI compilers, neither could fully unlock GPU performance or democratize AI compute. Instead, they reinforced silos: XLA remained TPU-centric, while TVM splintered into incompatible vendor-specific forks. They failed in the exact way CUDA alternatives were supposed to succeed!

Maybe the Triton “language” will save us?

But while these compilers struggled, a different approach was taking shape. Instead of trying to replace CUDA, it aimed to embrace GPU programming—while making it more programmable.

Enter Triton and the new wave of Python eDSLs—an attempt to bridge the gap between CUDA’s raw power and Python’s ease of use. In the next post, we’ll dive into these frameworks to see what they got right, where they fell short, and whether they finally broke free from the mistakes of the past.

Of course, you already know the answer. The CUDA Empire still reigns supreme. But why? And more importantly—what can we do about it?

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

—George Santayana

Perhaps one day, compiler technology will alleviate our suffering without taking away our power. Until next time, 🚀

Democratizing AI Compute, Part 7: What about Triton and Python eDSLs?

AI compilers struggle with a fundamental tradeoff: they aim to abstract low-level details for usability and scalability, yet modern GenAI workloads demand programmability and hardware control to deliver top performance. CUDA C++ provides this level of control, but it’s notoriously unwieldy and painful to use. Meanwhile, AI development happens in Python—so naturally, the industry has tried to bridge the gap by bringing GPU programming and Python together.

But there’s a catch: Python can’t run on a GPU. To bridge this gap, researchers build Embedded Domain-Specific Languages (eDSLs)—Python-based abstractions that look like Python but compile to efficient GPU code under the hood. The idea is simple: give engineers the power of CUDA without the pain of C++. But does it actually work?

In this post, we’ll break down how Python eDSLs work, their strengths and weaknesses, and take a close look at Triton—one of the most popular approaches in this space—and a few others. Can Python eDSLs deliver both performance and usability, or are they just another detour on the road to democratized AI compute?

Let’s dive in. 🚀

What’s an Embedded Domain Specific Language (eDSL)?

Domain Specific Languages are used when a specific domain has a unique way to express things that makes developers more productive—perhaps the most well known are HTML, SQL, and regular expressions. An “eDSL” is a DSL that re-uses an existing language’s syntax—but changes how the code works with compiler techniques. eDSLs power many systems, from distributed computing (PySpark) to deep learning frameworks (TensorFlow, PyTorch) to GPU programming (Triton).

For example, PySpark lets users express data transformations in Python, but constructs an optimized execution plan that runs efficiently across a cluster. Similarly, TensorFlow’s tf.function and PyTorch’s torch.fx convert Python-like code into optimized computation graphs. These eDSLs abstract away low-level details, making it easier to write efficient code without expertise in distributed systems, GPU programming, or compiler design.

How does an eDSL work?

eDSLs work their magic by capturing Python code before it runs and transforming it into a form they can process. They typically leverage decorators, a Python feature that intercepts functions before they run. When you apply @triton.jit, Python hands the function to Triton rather than executing it directly.

Here’s a simple Triton example:

@triton.jit

def kernel(x_ptr, y_ptr, BLOCK_SIZE: tl.constexpr):

offs = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE)

x = tl.load(x_ptr + offs)

tl.store(y_ptr + offs, x)

When Triton receives this code, it parses the function into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) that represents the function’s structure, including operations and data dependencies. This representation allows Triton to analyze patterns, apply optimizations, and generate efficient GPU code that performs the same operations.

By leveraging Python’s existing syntax and tooling, eDSL creators can focus on building compiler logic rather than designing an entirely new language with its own parser, syntax, and toolchain.

The advantage of eDSLs

eDSLs provide huge advantages for those building a domain-specific compiler: by embedding the language inside Python, developers can focus on compiler logic instead of reinventing an entire programming language. Designing new syntax, writing parsers, and building IDE tooling is a massive effort—by leveraging Python’s existing syntax and AST tools, eDSL creators skip all of that and get straight to solving the problem at hand.

Users of the eDSL benefit too: Python eDSLs let developers stay in familiar territory. They get to use the same Python IDEs, autocompletion, debugging tools, package managers (e.g. pip and conda), and ecosystem of libraries. Instead of learning a completely new language like CUDA C++, they write code in Python—and the eDSL guides execution under the hood.

However, this convenience comes with significant tradeoffs that can frustrate developers who expect eDSLs to behave like regular Python code.

The challenges with eDSLs

Of course, there’s no free lunch. eDSLs come with trade-offs, and some can be deeply frustrating.

It looks like Python, but it isn’t Python

This is the most confusing part of eDSLs. While the code looks like regular Python, it doesn’t behave like Python in crucial ways:

# Regular Python: This works as expected

def works():

kv = dict((i, i * i) for i in range(5))

return sum(kv.values())

# Python eDSL: The same code fails

@numba.njit()

def fails():

# Generator expressions aren't supported

kv = dict((i, i * i) for i in range(5))

# Built-in function sum isn't implemented

return sum(kv.values())

Why? Because an eDSL isn’t executing Python—it’s capturing and transforming the function into something else. It decides what constructs to support, and many everyday Python features (like dynamic lists, exception handling, or recursion) may simply not work. This can lead to silent failures or cryptic errors when something you’d expect to work in Python suddenly doesn’t.

Errors and Tooling Limitations

Debugging eDSL code can be a nightmare. When your code fails, you often don’t get the friendly Python error messages you’re used to. Instead, you’re staring at an opaque stack trace from deep inside of some compiler internals, with little clue what went wrong. Worse, standard tools like Python debuggers often don’t work at all, forcing you to rely on whatever debugging facilities the eDSL provides (if any). Further, while eDSLs exist within Python, they cannot use Python libraries directly.

Limited Expressiveness

eDSLs work by piggybacking on Python’s syntax, which means they can’t introduce new syntax that might be useful for their domain. A language like CUDA C++ can add custom keywords, new constructs, or domain-specific optimizations, while an eDSL is locked into a sublanguage of Python, which limits what it can express cleanly.

Ultimately, the quality of a specific eDSL determines how painful these trade-offs feel. A well-implemented eDSL can provide a smooth experience, while a poorly designed one can be a frustrating minefield of broken expectations. So does an eDSL like Triton get it right? And how does it compare to CUDA?

Triton: OpenAI’s Python eDSL for GPU Programming

Triton began as a research project from Philippe Tillet at Harvard University, first published in 2019 after years working on OpenCL (see my earlier post on OpenCL). The project gained significant momentum when Tillet joined OpenAI, and when PyTorch 2 decided to embrace it.

Unlike general-purpose AI compilers, Triton focuses on accessibility for Python developers while still allowing for deep optimization. It strikes a balance between high-level simplicity and low-level control—giving developers just enough flexibility to fine-tune performance without drowning in CUDA’s complexity.

Let’s explore what makes Triton so useful.

Block-centric programming model

Traditional GPU programming forces developers to think in terms of individual threads, managing synchronization and complex indexing by hand. Triton simplifies this by operating at the block level—where GPUs naturally perform their work—eliminating unnecessary low-level coordination:

@triton.jit

def simplified_kernel(input_ptr, output_ptr, n_elements, BLOCK_SIZE: tl.constexpr):

# One line gets us our block position

block_start = tl.program_id(0) * BLOCK_SIZE

# Create indexes for the entire block at once

offsets = block_start + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE)

# Process a whole block of data in one operation

data = tl.load(input_ptr + offsets, mask=offsets < n_elements)

# No need to worry about thread synchronization

This model abstracts away thread management and simplifies basic indexing, but it also makes it much easier to leverage TensorCores—the specialized hardware responsible for most of a GPU’s FLOPS:

# This simple dot product automatically uses TensorCores when available

result = tl.dot(matrix_a, matrix_b)

What would require dozens of lines of complex CUDA code becomes a single function call, while still achieving high performance. Triton handles the data layout transformations and hardware-specific optimizations automatically.

Simplified optimizations

One of CUDA’s most frustrating aspects is managing complex index calculations for multi-dimensional data. Triton dramatically simplifies this:

# Simple indexing with broadcast semantics

row_indices = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_M)[:, None]

col_indices = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_N)[None, :]

These array manipulations feel similar to NumPy but compile to efficient GPU code with no runtime overhead.

Triton also includes compiler-driven optimizations—like vectorization—and enables simplified double buffering and software pipelining, which overlap memory transfers with computation. In CUDA, these techniques require deep GPU expertise; in Triton, they’re exposed in a way that non-experts can actually use. For a deeper dive, OpenAI provides detailed tutorials.

Triton makes GPU programming far more accessible, but that accessibility comes with tradeoffs. Let’s take a look at some of the key challenges.

Where Triton Falls Short

Triton is widely used and very successful for some cases (e.g. researchers working on training frontier models and specialty use cases). However, it isn’t widely adopted for all applications: in particular, it’s not useful for AI inference use-cases, which require maximum efficiency. Furthermore, despite predictions years ago by industry leaders, Triton has not united the ecosystem or challenged CUDA’s dominance. Let’s dig in to understand the additional challenges Triton faces on top of the general limitations of all eDSLs (described earlier).

Significant GPU Performance/TCO Loss (compared to CUDA C++)

Triton trades performance for productivity (as explained by its creator). While this makes it easier to write GPU code, it also prevents Triton from achieving peak efficiency. The amount varies, but it is common to lose 20% on NVIDIA’s H100—which dominates AI compute today.

The problem? Compilers can’t optimize as well as a skilled CUDA developer, particularly for today’s advanced GPUs. In my decades of building compilers, I’ve never seen the myth of a “sufficiently smart compiler” actually work out! This is why leading AI labs, including DeepSeek, still rely on CUDA instead of Triton for demanding workloads: a 20% difference is untenable in GenAI: at scale it is the difference between a $1B cloud bill and an $800M one!

Governance: OpenAI’s Control and Focus

Triton is open source, but OpenAI owns its roadmap. That’s problematic because OpenAI competes directly with other frontier model labs, raising the question: will it prioritize the needs of the broader AI community, or just its own?